by Laurence Libin

Intersecting with cognition, music history, ethnomusicology, and engineering, my work as an organologist arose from curiosity about the expressive function of timbre and the nature of our responses to it, aspects thus far little studied compared to pitch, rhythm, and other fundamental building blocks. My path led from conventional schooling in performance (B.Mus., harpsichord, Northwestern University, 1966; private study with Paul Maynard and Thurston Dart) and musicology (M.Mus., King’s College, University of London, 1968; ABD, University of Chicago, 1972) to curating musical instruments for The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where I served for thirty-three years. I oversaw acquisition, conservation, and interpretation, the last area embracing exhibitions, recital and recording production, public lectures, and other educational programming that explored instruments from prehistory to the present. Concurrently I taught graduate courses and published papers in which I sought to explicate the process of innovation and show how the sounds and symbolism of different instruments affect compositional decisions and listeners’ reactions, often unconsciously.

After retiring from the Met, as president of the Organ Historical Society and honorary curator of Steinway & Sons, I was able to reach more specialized audiences through talks and publications outlining how technological, sociological, economic, and environmental forces as well as purely musical ones influence tonal design and expressive capabilities, particularly of keyboard instruments. I also consulted with cultural institutions that preserve rare instruments (including custodians of historic church organs) and advocated for their documentation and conservation. Finally, I was entrusted with editing the revisedGrove Dictionary of Musical Instruments (forthcoming in print in April 2014). I hope that the dictionary’s new coverage of such topics as haptics, ergonomic design, brain-computer interfaces, and found instruments will encourage interdisciplinary learning.

My formal training and hands-on employment with various instruments and situations (early on I tuned pianos, gave lessons, and played organ to pay the rent) led to career opportunities outside the normal scope of museum work and classroom teaching. No less valuable early experience, however, was organizing a tenant union, managing an apartment building, and negotiating with hostile landlords on Chicago’s rough South Side—useful preparation for work in non-profit institutions and commercial publishing.

The existence of close-knit societies for music theory, ethnomusicology, music perception, instrument buffs, and many other special-interest groups might suggest that we trespass with peril beyond narrowly defined disciplines. But venturesome forays outside traditional academic boundaries, armed with critical attitudes and skills gained from “real life,” can overcome this fragmentation and engage audiences in fresh ways of approaching music.

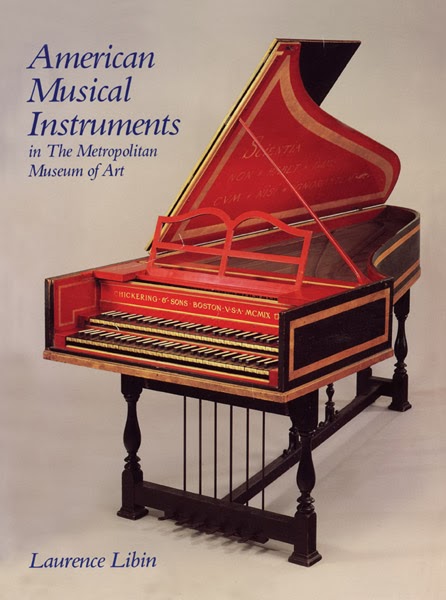

Laurence Libin is, well, all of the above. He was the curator of musical instruments at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for more than three decades, and founding chair of the AMS Committee on Non-Academic Employment (now the Committee on Career-Related Issues). His American Musical Instruments in The Metropolitan Museum of Art appeared in 2012 (Yale UP).

NOTE: The AMS Newsletter of the American Musicological Society features a series of reflections from musicologists who have pursued non-tenure-track careers. We are pleased to co-publish this essay from the February 2014 Newsletter.Beyond the immediate gratification music affords, listeners at all levels of sophistication seek deeper understanding of how music works and why it affects us—witness enthusiastic stories of the “Mozart effect” on child development. Research in music cognition is only in its infancy, but popular interest is growing, as shown by the eager reception accorded the insights of Oliver Sacks and other neuroscientists who are also able musicians. Modern technologies used in the study of music perception differ greatly from the tools of conventional music analysis; bridging this gap between radically contrasting approaches challenges the coming generation of musicologists, who will need new vocabularies and new skills to pursue a dialogue across fields often artificially separated in academe.

Intersecting with cognition, music history, ethnomusicology, and engineering, my work as an organologist arose from curiosity about the expressive function of timbre and the nature of our responses to it, aspects thus far little studied compared to pitch, rhythm, and other fundamental building blocks. My path led from conventional schooling in performance (B.Mus., harpsichord, Northwestern University, 1966; private study with Paul Maynard and Thurston Dart) and musicology (M.Mus., King’s College, University of London, 1968; ABD, University of Chicago, 1972) to curating musical instruments for The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where I served for thirty-three years. I oversaw acquisition, conservation, and interpretation, the last area embracing exhibitions, recital and recording production, public lectures, and other educational programming that explored instruments from prehistory to the present. Concurrently I taught graduate courses and published papers in which I sought to explicate the process of innovation and show how the sounds and symbolism of different instruments affect compositional decisions and listeners’ reactions, often unconsciously.

After retiring from the Met, as president of the Organ Historical Society and honorary curator of Steinway & Sons, I was able to reach more specialized audiences through talks and publications outlining how technological, sociological, economic, and environmental forces as well as purely musical ones influence tonal design and expressive capabilities, particularly of keyboard instruments. I also consulted with cultural institutions that preserve rare instruments (including custodians of historic church organs) and advocated for their documentation and conservation. Finally, I was entrusted with editing the revisedGrove Dictionary of Musical Instruments (forthcoming in print in April 2014). I hope that the dictionary’s new coverage of such topics as haptics, ergonomic design, brain-computer interfaces, and found instruments will encourage interdisciplinary learning.

My formal training and hands-on employment with various instruments and situations (early on I tuned pianos, gave lessons, and played organ to pay the rent) led to career opportunities outside the normal scope of museum work and classroom teaching. No less valuable early experience, however, was organizing a tenant union, managing an apartment building, and negotiating with hostile landlords on Chicago’s rough South Side—useful preparation for work in non-profit institutions and commercial publishing.

The existence of close-knit societies for music theory, ethnomusicology, music perception, instrument buffs, and many other special-interest groups might suggest that we trespass with peril beyond narrowly defined disciplines. But venturesome forays outside traditional academic boundaries, armed with critical attitudes and skills gained from “real life,” can overcome this fragmentation and engage audiences in fresh ways of approaching music.

Laurence Libin is, well, all of the above. He was the curator of musical instruments at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for more than three decades, and founding chair of the AMS Committee on Non-Academic Employment (now the Committee on Career-Related Issues). His American Musical Instruments in The Metropolitan Museum of Art appeared in 2012 (Yale UP).