by John Covach

New York promoter Sid Bernstein called himself “the man who brought the Beatles to America.”<1> Bernstein’s oft-told story of how he came to book the Beatles for two performances in Carnegie Hall on February 12, 1964, however, has been questioned by at least one expert.<2> The chief point of contention regarding Bernstein’s account is that he booked the Beatles before Ed Sullivan approached them to appear on his Sunday-night variety show. The Beatles appeared on Sullivan’s show three weeks in a row; the first broadcast on February 9—fifty years ago this Sunday—is regarded as historic, drawing more than 70 million viewers and launching the British invasion. A closer look at Bernstein’s story, as well as the one told by Sullivan, reveals that there is likely an element of show-biz fish tale in both. But a broader understanding of the career circumstances surrounding the Beatles in fall of 1963 suggests a likely scenario that preserves the main thrust of both stories and corrects the errors found so frequently in current media accounts.

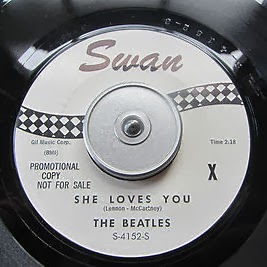

In January 1963, the Beatles’ second single, “Please Please Me,” hit the top of the UK charts. As the year progressed, the band landed two more singles at the top of the British charts, “From Me to You” (April) and “She Loves You” (August), as well as enjoying a number-one album with Please Please Me (March). In October the group appeared on Sunday Night at the London Palladium and on the Royal Variety Performance broadcast in November, two television appearances that secured their star status in the UK just as their fifth single, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and the album With the Beatles both went to number one (late 1963). As the band’s success increased throughout 1963, Beatles manager Brian Epstein began to focus on how to translate this British success to the US. The group recorded for Parlophone, a division of EMI; the Capitol record label in Los Angeles was owned by EMI. Despite this connection, the American heads of Capitol refused to release the first four Beatles singles (including the first, “Love Me Do”), arguing that Americans simply would not be interested in a British pop group.<3> Rejected by Capitol, “Please Please Me” and “From Me to You” appeared on Vee Jay, and “She Loves You” appeared on Swan. All three records initially flopped in the US.<4>

In late summer or early fall 1963, however, three potential business partners were beginning to cluster around Epstein and the Beatles, all seeing tremendous American promise in the group’s UK success. At the London office of United Artists Records, Noel Rodgers noticed that the band’s exclusive contract with EMI did not seem to cover soundtrack albums. He took this information to UA’s European head Bud Ornstein, and Ornstein was able to spearhead a deal with Epstein to make a Beatles movie. As far as UA was concerned, the film could actually lose money so long as the resulting album was a hit.<5> When the Beatles broke in the US in January 1964, Ornstein looked like a genius: that summer, far from being a promotional vehicle for the soundtrack album, the film A Hard Day’s Night became a significant box-office hit in its own right.

During the same period, one of Ed Sullivan’s UK-based talent scouts, Peter Prichard, was reporting back to New York on the rise of Beatlemania. Sullivan himself had been in London in September and visited with Prichard, who then sent Sullivan press clippings on the band. When the Beatles returned to London’s Heathrow Airport from Sweden on October 31, the runway had to be shut down for a period to ensure that the throng of enthusiastic fans remained safe. Sullivan sometimes told the story that he was sitting in a plane on the runway and upon learning about the Beatles popularity, decided at that moment to book them. However, evidence casts doubt on whether Sullivan was actually in that plane that day. While he was at Heathrow in September, he was most likely in New York on October 31.<6> By this time Prichard had already contacted Epstein about the possibility of booking the Beatles for Sullivan’s show anyway, and in early November, Brian flew to New York and locked down the deal for the three shows in February.

This context sheds light on the story told by Sid Bernstein. Bernstein claims to have contacted Epstein in the spring of 1963. While this is possible, it is more likely that the contact was made in November, since Bernstein names Bud Halliwell as the person who provided Epstein’s number, and Halliwell was in contact with Epstein at about that time to assist in the promotion of Beatles records.<7> Epstein would have been eager to sign the movie deal with UA and the television deal with Sullivan before the Beatles had a hit in the US because both of those could be thought of as promotion. He hesitated on the Carnegie Hall concerts, however, because without a hit single in the US the band might play to a half-filled house—or worse. When Washington D.C.’s WWDC radio began playing a UK copy of “I Want To Hold Your Hand” in mid-December, the record became hot and Capitol decided to move the release date up to December 26 from the mid-January date they had finally been talked into by EMI. By mid-January it was clear the record was a hit. Epstein likely confirmed the Carnegie Hall show with Bernstein then at the latest, though perhaps as early as December, and booked a warm-up show in the nation’s capital for February 11. This warm-up show ended up being filmed by CBS, appearing in theaters across the US in March 1964, months before the premiere of A Hard Day’s Night. Capitol even attempted to record the Carnegie Hall shows, but the plans were dashed when the American Federation of Musicians would not permit the Beatles’ British producer George Martin to supervise the work.

In light of this context, then, it seems likely that Bernstein did not get a commitment out of Epstein before Sullivan booked the Beatles, though he did know enough about the group to book them before they had a hit single. It also is clear that Sullivan took a chance on a band unknown in the US, signing them to three consecutive appearances on his high-profile show. The signing of the film agreement with UA in the fall of 1963 further establishes that all of these deals were meant to break the Beatles in America on the promise of their UK success. When the Beatles got word that “I Want to Hold Your Hand” had gone to number one on the Cashbox charts in late January, they were performing a series of shows in Paris, attempting to build their following in France. During their time in Paris, they also went into the studio to re-record the vocals to “I Want To Hold Your Hand” and “She Loves You” in German, in hopes of boosting their German following. Having a hit single in the US came as a big and very pleasant surprise to the band, eclipsing anything they could have done for themselves in France and Germany. In the end, Ornstein’s, Sullivan’s, and Bernstein’s bets paid off and Epstein successfully engineered and executed a plan to storm America. The British invasion was on.

John Covach is Director of the Institute for Popular Music at the University of Rochester, where he is also the Mercer Brugler Distinguished Teaching Professor and Professor of Theory at the Eastman School of Music.

NOTES

1. Bernstein tells the story in his autobiography, “It’s Sid Bernstein Calling”. . . The Amazing Story of the Promoter Who Made Entertainment History, as told to Arthur Aaron (Middle Village, New York: Jonathan David, 2002), 111–56. Versions of the story appear in Bill Harry, The British Invasion: How the Beatles and Other UK Bands Conquered America (Surrey: Chrome Dreams, 2004) and Ray Coleman, The Man Who Made the Beatles: An Intimate Biography of Brian Epstein (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989). Both Harry and Coleman knew the Beatles and Brian Epstein during these early days ,and neither seems to have found Bernstein’s story untenable or far-fetched.

2. Bruce Spizer, The Beatles Are Coming: The Birth of the British Invasion in America (New Orleans: 498 Productions, 2003), 188–89. Spizer’s evidence challenging Bernstein’s claim is strong but not conclusive.

3. Though this judgment turned out to be wrong in the case of the Beatles, it was entirely justified. Aside from The Tornadoes’ “Telstar,” which went to number one in the US in 1962, very little British rock had any success stateside.

4. Capitol did actually reject “From Me To You,” since the Vee Jay deal for “Please Please Me” gave the smaller label right of first refusal on future Beatles recordings. EMI broke with Vee Jay over on-payment of royalties and as a result “She Loves You” was offered to Capitol, who rejected it. Meanwhile Capitol in Canada, led by Paul White, released all three of these songs plus “Love Me Do.” These first three Canadian singles did very poorly, seemingly confirming the Capitol US decision; “She Loves You,” on the other hand, did very well in the north, prompting sales of the previous releases in its wake. “She Loves You” was a hit in Canada in December of 1963, a week before “I Want To Hold Your Hand” was released in the US.

5. Ray Morton, Music on Film: A Hard Day’s Night (Milwaukee: Limelight Editions, 2011), 16–18.

6. James Maguire, Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (New York: Billboard Books, 2008), 281-96. The October 31 Heathrow event did occur, but Maguire argues that Sullivan probably wasn’t there.

7. Spizer reports that Epstein hired Halliwell (Spizer spells the name “Helliwell”) in November, when he went to New York to meet with Sullivan. See Spizer, p. 189, and Bernstein, p. 116.

In January 1963, the Beatles’ second single, “Please Please Me,” hit the top of the UK charts. As the year progressed, the band landed two more singles at the top of the British charts, “From Me to You” (April) and “She Loves You” (August), as well as enjoying a number-one album with Please Please Me (March). In October the group appeared on Sunday Night at the London Palladium and on the Royal Variety Performance broadcast in November, two television appearances that secured their star status in the UK just as their fifth single, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and the album With the Beatles both went to number one (late 1963). As the band’s success increased throughout 1963, Beatles manager Brian Epstein began to focus on how to translate this British success to the US. The group recorded for Parlophone, a division of EMI; the Capitol record label in Los Angeles was owned by EMI. Despite this connection, the American heads of Capitol refused to release the first four Beatles singles (including the first, “Love Me Do”), arguing that Americans simply would not be interested in a British pop group.<3> Rejected by Capitol, “Please Please Me” and “From Me to You” appeared on Vee Jay, and “She Loves You” appeared on Swan. All three records initially flopped in the US.<4>

In late summer or early fall 1963, however, three potential business partners were beginning to cluster around Epstein and the Beatles, all seeing tremendous American promise in the group’s UK success. At the London office of United Artists Records, Noel Rodgers noticed that the band’s exclusive contract with EMI did not seem to cover soundtrack albums. He took this information to UA’s European head Bud Ornstein, and Ornstein was able to spearhead a deal with Epstein to make a Beatles movie. As far as UA was concerned, the film could actually lose money so long as the resulting album was a hit.<5> When the Beatles broke in the US in January 1964, Ornstein looked like a genius: that summer, far from being a promotional vehicle for the soundtrack album, the film A Hard Day’s Night became a significant box-office hit in its own right.

During the same period, one of Ed Sullivan’s UK-based talent scouts, Peter Prichard, was reporting back to New York on the rise of Beatlemania. Sullivan himself had been in London in September and visited with Prichard, who then sent Sullivan press clippings on the band. When the Beatles returned to London’s Heathrow Airport from Sweden on October 31, the runway had to be shut down for a period to ensure that the throng of enthusiastic fans remained safe. Sullivan sometimes told the story that he was sitting in a plane on the runway and upon learning about the Beatles popularity, decided at that moment to book them. However, evidence casts doubt on whether Sullivan was actually in that plane that day. While he was at Heathrow in September, he was most likely in New York on October 31.<6> By this time Prichard had already contacted Epstein about the possibility of booking the Beatles for Sullivan’s show anyway, and in early November, Brian flew to New York and locked down the deal for the three shows in February.

This context sheds light on the story told by Sid Bernstein. Bernstein claims to have contacted Epstein in the spring of 1963. While this is possible, it is more likely that the contact was made in November, since Bernstein names Bud Halliwell as the person who provided Epstein’s number, and Halliwell was in contact with Epstein at about that time to assist in the promotion of Beatles records.<7> Epstein would have been eager to sign the movie deal with UA and the television deal with Sullivan before the Beatles had a hit in the US because both of those could be thought of as promotion. He hesitated on the Carnegie Hall concerts, however, because without a hit single in the US the band might play to a half-filled house—or worse. When Washington D.C.’s WWDC radio began playing a UK copy of “I Want To Hold Your Hand” in mid-December, the record became hot and Capitol decided to move the release date up to December 26 from the mid-January date they had finally been talked into by EMI. By mid-January it was clear the record was a hit. Epstein likely confirmed the Carnegie Hall show with Bernstein then at the latest, though perhaps as early as December, and booked a warm-up show in the nation’s capital for February 11. This warm-up show ended up being filmed by CBS, appearing in theaters across the US in March 1964, months before the premiere of A Hard Day’s Night. Capitol even attempted to record the Carnegie Hall shows, but the plans were dashed when the American Federation of Musicians would not permit the Beatles’ British producer George Martin to supervise the work.

In light of this context, then, it seems likely that Bernstein did not get a commitment out of Epstein before Sullivan booked the Beatles, though he did know enough about the group to book them before they had a hit single. It also is clear that Sullivan took a chance on a band unknown in the US, signing them to three consecutive appearances on his high-profile show. The signing of the film agreement with UA in the fall of 1963 further establishes that all of these deals were meant to break the Beatles in America on the promise of their UK success. When the Beatles got word that “I Want to Hold Your Hand” had gone to number one on the Cashbox charts in late January, they were performing a series of shows in Paris, attempting to build their following in France. During their time in Paris, they also went into the studio to re-record the vocals to “I Want To Hold Your Hand” and “She Loves You” in German, in hopes of boosting their German following. Having a hit single in the US came as a big and very pleasant surprise to the band, eclipsing anything they could have done for themselves in France and Germany. In the end, Ornstein’s, Sullivan’s, and Bernstein’s bets paid off and Epstein successfully engineered and executed a plan to storm America. The British invasion was on.

John Covach is Director of the Institute for Popular Music at the University of Rochester, where he is also the Mercer Brugler Distinguished Teaching Professor and Professor of Theory at the Eastman School of Music.

NOTES

1. Bernstein tells the story in his autobiography, “It’s Sid Bernstein Calling”. . . The Amazing Story of the Promoter Who Made Entertainment History, as told to Arthur Aaron (Middle Village, New York: Jonathan David, 2002), 111–56. Versions of the story appear in Bill Harry, The British Invasion: How the Beatles and Other UK Bands Conquered America (Surrey: Chrome Dreams, 2004) and Ray Coleman, The Man Who Made the Beatles: An Intimate Biography of Brian Epstein (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989). Both Harry and Coleman knew the Beatles and Brian Epstein during these early days ,and neither seems to have found Bernstein’s story untenable or far-fetched.

2. Bruce Spizer, The Beatles Are Coming: The Birth of the British Invasion in America (New Orleans: 498 Productions, 2003), 188–89. Spizer’s evidence challenging Bernstein’s claim is strong but not conclusive.

3. Though this judgment turned out to be wrong in the case of the Beatles, it was entirely justified. Aside from The Tornadoes’ “Telstar,” which went to number one in the US in 1962, very little British rock had any success stateside.

4. Capitol did actually reject “From Me To You,” since the Vee Jay deal for “Please Please Me” gave the smaller label right of first refusal on future Beatles recordings. EMI broke with Vee Jay over on-payment of royalties and as a result “She Loves You” was offered to Capitol, who rejected it. Meanwhile Capitol in Canada, led by Paul White, released all three of these songs plus “Love Me Do.” These first three Canadian singles did very poorly, seemingly confirming the Capitol US decision; “She Loves You,” on the other hand, did very well in the north, prompting sales of the previous releases in its wake. “She Loves You” was a hit in Canada in December of 1963, a week before “I Want To Hold Your Hand” was released in the US.

5. Ray Morton, Music on Film: A Hard Day’s Night (Milwaukee: Limelight Editions, 2011), 16–18.

6. James Maguire, Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (New York: Billboard Books, 2008), 281-96. The October 31 Heathrow event did occur, but Maguire argues that Sullivan probably wasn’t there.

7. Spizer reports that Epstein hired Halliwell (Spizer spells the name “Helliwell”) in November, when he went to New York to meet with Sullivan. See Spizer, p. 189, and Bernstein, p. 116.