Musicology Now is pleased to welcome Christopher J. Smith to our editorial team. Smith is Professor, Chair of Musicology, and director of the Vernacular Music Center at the Texas Tech University School of Music. His research interests are in African-American Music, 20th Century Music, Irish traditional music and other vernaculars, improvisation, music and politics, and historical performance. He records and tours with Altramar medieval music ensemble, the Irish traditional band Last Night’s Fun, the Juke Band (pre-WWII blues and jazz), and the pan-European Balfolk group Rattleskull. His full-length theatrical dance show Dancing at the Crossroads premiered in February 2013 and his scholarly monograph, The Creolization of American Culture: William Sidney Mount and the Roots of Blackface Minstrelsy (Illinois), was the winner of the Irving Lowens award from the Society for American Music in 2013. Smith's new monograph for Illinois is Movement Revolutions: Bodies, Spaces, and Noise in American Cultural History (2019). He is the Executive Editor of the peer-reviewed Journal of the Vernacular Music Center, directs the TTU Celtic Ensemble, and arranges for and conducts the Elegant Savages Orchestra symphonic folk group at Texas Tech. He is a former nightclub bouncer, framing carpenter, lobster fisherman, and oil-rig roughneck, and a published poet.

↧

Musicology Now Welcomes Christopher J. Smith

↧

Global Perspectives—The Art of Derivation: Jo Kondo’s Paregmenon

By Anton Vishio

“Paregmenon is a figure which of the word going before deriveth the word following.” So Henry Peacham defined the rhetorical device, in one of the word’s earliest English attestations.<1> Paregmenon was originally a participial form of an Ancient Greek verb whose basic meaning of “to lead by or past a place” spawned a number of metaphorical extensions—including ones which involved the path a word might take to become another. In its English borrowing, the term came to be applied specifically to describe root-related words deployed in proximity. Peacham cites a classic biblical example: “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise.” His contemporaries made ample use of the device, sometimes in combination with other techniques, as in Measure to Measure: “To sue I live, I find I seek to die, And seeking death, find life”.<2>

But Peacham also goes on to assess the effects of such rhetoric. Of paregmenon, he wrote: “The use hereof is twofold, to delight the eare by the derived sound, and to move the mind with a consideration of the nigh affinitie and concord of the matter.” This could serve as a description of the manifold pleasures that Jo Kondo’s music makes available to its listeners. Kondo has pursued a similar compositional art of juxtaposition—the “affinitie and concord” of sounds placed aside one another—as a means to capture in music the effect of an apparently “flat surface” that is nonetheless perceptually active. This creates what Kondo refers to, relishing the apparent contradiction, as “dynamic stasis.” Surveying the scarred landscape of Dartmoor, Kondo experienced a similar assemblage in the visual domain, a “patchwork of green rocks and reddish earth, none of them being confined to the foreground or background”.<3> There is no obvious path through such a landscape; rather we might just discern a way forwards, driven by subtle shifts in the local equilibrium suggested to us by the placement of similar materials—by attention, that is, to their common derivation.

In choosing Paregmenon as the title of his 2011 composition for combined string and percussion quartets, Kondo thus gave expression to a distinctive aesthetic preoccupation.<4> The title seems relevant in another way, in relation to the composer’s avowed interest in Hellenistic thought, and even in connection to his self-identification with a “Western music world” as opposed to a specifically Japanese one.<5> For his engagement with the former sometimes reveals itself at an angle, and paregmenon enters even at this level; several of the descriptors that Kondo applies to his own music themselves appear to be rooted in yet subtly branch off from familiar Western music theoretical concepts, including as we shall see such fundamental ideas as line and form.

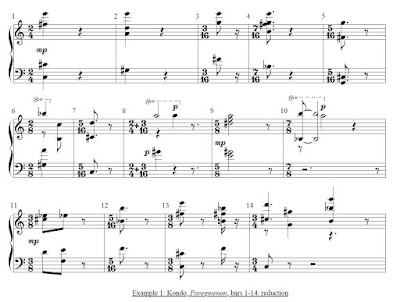

Kondo observes that his musical paregmenon relies on successions of shared “root intervals”.<6> Example 1 presents a reduced score of the first fourteen measures. The succession unfolds slowly, so that each sonic object can be savored for its distinctive configuration. To take Peacham’s definition literally, it is as if we are inside each unfolding paregmenon, experiencing its derivation from within. The first sonority in this context would seem an especially fruitful starting point; it voices an all-interval tetrachord, rich in potential “roots.” But even more palpable connections between sonorities are available to our audition. The use of common tones, a preference for minor ninths and their compounds, and recurrent semitone-tritone complexes are all features that one might take up in a more extensive analysis. The instrumental disposition of the work—a joining together of two disparate ‘instruments’ to create a third that, as Kondo notes, is somehow different from both—is no less involved in the collocating of sonorities. Example 2 reproduces the same music, but with attention to the actual scoring. Initially, we have the sense that each pitch pairs an instrument from each quartet, but this is quickly destabilized. A myriad of evanescent linear connections emanates from these pitch and timbral connections, in what Kondo terms a “pseudo-polyphony.”<7>

In this terrain of constant change, what does it mean for a sonority to recur? Indeed, the first sonority reappears, with only slight adjustment, on the downbeat of measure 13. Similar repetitions are seeded into the fabric of the composition, as they are in Kondo’s music in general; the act of juxtaposition can lead us in many directions, including apparently back to where we started.<8> Such events ward off a hearing which pays no heed to memory. Kondo’s music requires us to be alert to—and wary of—the constant possibility of renewing our path through recollection of its previous states. Indeed, recollection is as much a part of the experience of paregmenon as derivation. While listening, we are navigating a middle course between the experience of literal repetition and variation, what Kondo refers to as “pseudo-repetition.”<9> This pseudo-repetition suggests a particular approach to the reconstructive capacity of memory that aligns with the occasionally more humbling aspects of the experience: Kondo’s paregemenons destabilize the object one might remember. Certainty is always in question, and the possibility of error is constantly before us, just as it is in the practice of real memory.

Despite its richly connected surface, this opening music moves through a dizzying array of close or distant sonorities with no regular pulse beyond a constant pushing and pulling of chordal interactions. There is no single organizing reference, no textural center. Borrowing a term from William Caplin, we can refer to this music as manifesting ‘loose’ organization. His term becomes even more useful when we discover, later in the composition, the music suddenly aligning into a contrasting, ‘tight-knit’ pattern that features a dialogue in the style of a frieze pattern between alternating marimba duo and string quartet, about an insistent, refrain-like figure in the vibraphone.<10> The second such passage is shown on example 3. The intervals in the refrain seem responsive to the intervallic content of the duo and quartet, suggesting that a “root interval” may be derived from a process of distillation. At core, such a context allows us yet another format in which to experience the affinities at the heart of paregmenon; the anxieties of an unfamiliar terrain have given way to a sense of wonder at its fragile beauty.

***

<1> Peacham’s Garden of Eloquence appeared first in 1577; I’ve used the slightly changed definition from the 1593 edition, available online at http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/collection?collection=Perseus%3Acollection%3APeachum_Garden (accessed January 10, 2018). The original wording appears in the OED. (His last name is occasionally spelled “Peachum”.)

<2> Peacham sources the Biblical example from Isaiah, although in this paraphrased form it appears in 1 Corinthians. The Shakespeare example comes from Jean-Marie Maguin’s useful catalogue, “Words as the Measure of Measure for Measure”: Shakespeare’s Use of Rhetoric in the Play”, Sillages critiques 15 (2013), at http://journals.openedition.org/sillagescritiques/2618?gathStatIcon=true&lang=en (accessed January 10, 2018).

<3> Kondo, liner notes for CD ALCD-57 (2000); the disc contains his Trio (moor), from 1982. For the landscape itself, see for instance the second picture at https://historicengland.org.uk/research/research-results/recent-research-results/south-west/dartmoor-nmp/ (accessed January 10, 2018).

<4> The work was premiered by the Quatuor Bozzini and Slagwerk Den Haag in November 2011. Unfortunately, there is no commercial recording available.

Kondo has recently commented on the properties of his titles: “When I give a name to a sound structure, I consider very carefully: if the sound construction has this name, what psychological image does it evoke in the listener?” Interview with Barbara Eckle, appearing in the liner notes to Wergo CD WER 7342 2 (2016)

<5> Personal communication; see also the composer’s dialogue with Stefan van Eycken that followed the premiere of Paregmenon: https://slagwerkdenhaag.wordpress.com/2012/01/04/interview-jo-kondo-stefan-van-eycken/ at 4:27 (accessed January 11, 2018). This is not a negative assessment by any means; he acknowledges that being Japanese undoubtedly affects his musical voice, but he has chosen to leave this unanalyzed. For an example of a recent attempt to link Kondo’s musical personality to specifically Japanese concepts, see John Liberatore, “Mutual Relationships: an Aesthetic Analysis of Jo Kondo’s High Window”, DMA dissertation, Eastman (2014): 24-28.

<6> Dialogue with van Eycken, at 2:14. In music theory, “root intervals” usually refers to the intervals between the roots of successive triads, a topic studied rigorously in contemporary neo-Riemannian theory; Kondo’s use is unrelated.

<7> An excellent introduction to “pseudo-polyphony” can be found in Liberatore, op. cit., 8-11.

<8> A reading of Kondo’s music particularly sensitive to the effects of different kinds of repetition is Paul Zukofsky’s essay, “Jo Kondo’s Still Life”, available at http://www.musicalobservations.com/publications/jo_kondos_still_life/ (accessed March 3, 2018).

<9> Kondo, “The Art of Being Ambiguous: From Listening to Composing,” Contemporary Music Review 2: 2 (1988), 7-29. The definition and related discussion are on pages 25-26.

<10> This alignment is all the more striking following some extremely fast music, in Kondo’s sen no ongaku [linear music] style. I borrow the ‘loose’ vs. ‘tight-knit’ distinction from Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

***

![]() Anton Vishio is an Assistant Professor at William Paterson University in Wayne, NJ, where he teaches music theory and composition. His research involves analysis of a variety of composers of late 20th century music; recent papers have explored works by George Lewis, Priaulx Rainier, Brian Cherney, and Milton Babbitt.

Anton Vishio is an Assistant Professor at William Paterson University in Wayne, NJ, where he teaches music theory and composition. His research involves analysis of a variety of composers of late 20th century music; recent papers have explored works by George Lewis, Priaulx Rainier, Brian Cherney, and Milton Babbitt.

“Paregmenon is a figure which of the word going before deriveth the word following.” So Henry Peacham defined the rhetorical device, in one of the word’s earliest English attestations.<1> Paregmenon was originally a participial form of an Ancient Greek verb whose basic meaning of “to lead by or past a place” spawned a number of metaphorical extensions—including ones which involved the path a word might take to become another. In its English borrowing, the term came to be applied specifically to describe root-related words deployed in proximity. Peacham cites a classic biblical example: “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise.” His contemporaries made ample use of the device, sometimes in combination with other techniques, as in Measure to Measure: “To sue I live, I find I seek to die, And seeking death, find life”.<2>

But Peacham also goes on to assess the effects of such rhetoric. Of paregmenon, he wrote: “The use hereof is twofold, to delight the eare by the derived sound, and to move the mind with a consideration of the nigh affinitie and concord of the matter.” This could serve as a description of the manifold pleasures that Jo Kondo’s music makes available to its listeners. Kondo has pursued a similar compositional art of juxtaposition—the “affinitie and concord” of sounds placed aside one another—as a means to capture in music the effect of an apparently “flat surface” that is nonetheless perceptually active. This creates what Kondo refers to, relishing the apparent contradiction, as “dynamic stasis.” Surveying the scarred landscape of Dartmoor, Kondo experienced a similar assemblage in the visual domain, a “patchwork of green rocks and reddish earth, none of them being confined to the foreground or background”.<3> There is no obvious path through such a landscape; rather we might just discern a way forwards, driven by subtle shifts in the local equilibrium suggested to us by the placement of similar materials—by attention, that is, to their common derivation.

In choosing Paregmenon as the title of his 2011 composition for combined string and percussion quartets, Kondo thus gave expression to a distinctive aesthetic preoccupation.<4> The title seems relevant in another way, in relation to the composer’s avowed interest in Hellenistic thought, and even in connection to his self-identification with a “Western music world” as opposed to a specifically Japanese one.<5> For his engagement with the former sometimes reveals itself at an angle, and paregmenon enters even at this level; several of the descriptors that Kondo applies to his own music themselves appear to be rooted in yet subtly branch off from familiar Western music theoretical concepts, including as we shall see such fundamental ideas as line and form.

Kondo observes that his musical paregmenon relies on successions of shared “root intervals”.<6> Example 1 presents a reduced score of the first fourteen measures. The succession unfolds slowly, so that each sonic object can be savored for its distinctive configuration. To take Peacham’s definition literally, it is as if we are inside each unfolding paregmenon, experiencing its derivation from within. The first sonority in this context would seem an especially fruitful starting point; it voices an all-interval tetrachord, rich in potential “roots.” But even more palpable connections between sonorities are available to our audition. The use of common tones, a preference for minor ninths and their compounds, and recurrent semitone-tritone complexes are all features that one might take up in a more extensive analysis. The instrumental disposition of the work—a joining together of two disparate ‘instruments’ to create a third that, as Kondo notes, is somehow different from both—is no less involved in the collocating of sonorities. Example 2 reproduces the same music, but with attention to the actual scoring. Initially, we have the sense that each pitch pairs an instrument from each quartet, but this is quickly destabilized. A myriad of evanescent linear connections emanates from these pitch and timbral connections, in what Kondo terms a “pseudo-polyphony.”<7>

In this terrain of constant change, what does it mean for a sonority to recur? Indeed, the first sonority reappears, with only slight adjustment, on the downbeat of measure 13. Similar repetitions are seeded into the fabric of the composition, as they are in Kondo’s music in general; the act of juxtaposition can lead us in many directions, including apparently back to where we started.<8> Such events ward off a hearing which pays no heed to memory. Kondo’s music requires us to be alert to—and wary of—the constant possibility of renewing our path through recollection of its previous states. Indeed, recollection is as much a part of the experience of paregmenon as derivation. While listening, we are navigating a middle course between the experience of literal repetition and variation, what Kondo refers to as “pseudo-repetition.”<9> This pseudo-repetition suggests a particular approach to the reconstructive capacity of memory that aligns with the occasionally more humbling aspects of the experience: Kondo’s paregemenons destabilize the object one might remember. Certainty is always in question, and the possibility of error is constantly before us, just as it is in the practice of real memory.

Despite its richly connected surface, this opening music moves through a dizzying array of close or distant sonorities with no regular pulse beyond a constant pushing and pulling of chordal interactions. There is no single organizing reference, no textural center. Borrowing a term from William Caplin, we can refer to this music as manifesting ‘loose’ organization. His term becomes even more useful when we discover, later in the composition, the music suddenly aligning into a contrasting, ‘tight-knit’ pattern that features a dialogue in the style of a frieze pattern between alternating marimba duo and string quartet, about an insistent, refrain-like figure in the vibraphone.<10> The second such passage is shown on example 3. The intervals in the refrain seem responsive to the intervallic content of the duo and quartet, suggesting that a “root interval” may be derived from a process of distillation. At core, such a context allows us yet another format in which to experience the affinities at the heart of paregmenon; the anxieties of an unfamiliar terrain have given way to a sense of wonder at its fragile beauty.

***

<1> Peacham’s Garden of Eloquence appeared first in 1577; I’ve used the slightly changed definition from the 1593 edition, available online at http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/collection?collection=Perseus%3Acollection%3APeachum_Garden (accessed January 10, 2018). The original wording appears in the OED. (His last name is occasionally spelled “Peachum”.)

<2> Peacham sources the Biblical example from Isaiah, although in this paraphrased form it appears in 1 Corinthians. The Shakespeare example comes from Jean-Marie Maguin’s useful catalogue, “Words as the Measure of Measure for Measure”: Shakespeare’s Use of Rhetoric in the Play”, Sillages critiques 15 (2013), at http://journals.openedition.org/sillagescritiques/2618?gathStatIcon=true&lang=en (accessed January 10, 2018).

<3> Kondo, liner notes for CD ALCD-57 (2000); the disc contains his Trio (moor), from 1982. For the landscape itself, see for instance the second picture at https://historicengland.org.uk/research/research-results/recent-research-results/south-west/dartmoor-nmp/ (accessed January 10, 2018).

<4> The work was premiered by the Quatuor Bozzini and Slagwerk Den Haag in November 2011. Unfortunately, there is no commercial recording available.

Kondo has recently commented on the properties of his titles: “When I give a name to a sound structure, I consider very carefully: if the sound construction has this name, what psychological image does it evoke in the listener?” Interview with Barbara Eckle, appearing in the liner notes to Wergo CD WER 7342 2 (2016)

<5> Personal communication; see also the composer’s dialogue with Stefan van Eycken that followed the premiere of Paregmenon: https://slagwerkdenhaag.wordpress.com/2012/01/04/interview-jo-kondo-stefan-van-eycken/ at 4:27 (accessed January 11, 2018). This is not a negative assessment by any means; he acknowledges that being Japanese undoubtedly affects his musical voice, but he has chosen to leave this unanalyzed. For an example of a recent attempt to link Kondo’s musical personality to specifically Japanese concepts, see John Liberatore, “Mutual Relationships: an Aesthetic Analysis of Jo Kondo’s High Window”, DMA dissertation, Eastman (2014): 24-28.

<6> Dialogue with van Eycken, at 2:14. In music theory, “root intervals” usually refers to the intervals between the roots of successive triads, a topic studied rigorously in contemporary neo-Riemannian theory; Kondo’s use is unrelated.

<7> An excellent introduction to “pseudo-polyphony” can be found in Liberatore, op. cit., 8-11.

<8> A reading of Kondo’s music particularly sensitive to the effects of different kinds of repetition is Paul Zukofsky’s essay, “Jo Kondo’s Still Life”, available at http://www.musicalobservations.com/publications/jo_kondos_still_life/ (accessed March 3, 2018).

<9> Kondo, “The Art of Being Ambiguous: From Listening to Composing,” Contemporary Music Review 2: 2 (1988), 7-29. The definition and related discussion are on pages 25-26.

<10> This alignment is all the more striking following some extremely fast music, in Kondo’s sen no ongaku [linear music] style. I borrow the ‘loose’ vs. ‘tight-knit’ distinction from Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

***

Anton Vishio is an Assistant Professor at William Paterson University in Wayne, NJ, where he teaches music theory and composition. His research involves analysis of a variety of composers of late 20th century music; recent papers have explored works by George Lewis, Priaulx Rainier, Brian Cherney, and Milton Babbitt.

Anton Vishio is an Assistant Professor at William Paterson University in Wayne, NJ, where he teaches music theory and composition. His research involves analysis of a variety of composers of late 20th century music; recent papers have explored works by George Lewis, Priaulx Rainier, Brian Cherney, and Milton Babbitt.

↧

↧

Global Perspectives—The Story of Unsuk Chin’s Cello Concerto

By Jung-Min Lee

Unsuk Chin, born in South Korea and now based in Germany, has only occasionally engaged with traditional Korean or Asian music. Among a handful of examples is the last movement of Akrostichon-Wortspiel (1991), titled “Aus der alten Zeit,” described as “an ironic commentary on the traditional Korean court music” (it is left to the listeners to determine which features are based on Korean music and why they are “ironic.”)<1> She also wrote for the traditional Chinese instrument sheng in Šu for sheng and orchestra in 2009. She emphasized, however, that her motivation to write for a traditional Asian instrument was the new sound possibilities revealed in the playing of the virtuoso sheng player Wu Wei, rather than a broader interest in mixing Asian and Western music. The first movement of Chin’s Cello Concerto, written in 2008 and revised in 2013, is a rare case in which she refers to specific element of Korean traditional music, with the subtitle “Aniri.” Yet Chin has not explained what that subtitle means, or how it relates to the movement, leaving it up to listeners and performers to make their own interpretations.

Let me first introduce the term aniri, before offering a reading of how it may explain a structural aspect of the first movement of the Cello Concerto. Aniri is an element of the Korean traditional vocal genre pansori, a narrative epic drama performed by a vocalist, soriggun, and a percussionist, gosu. The vocalist tells a story through singing (sori), speech (aniri) and theatrical gestures (nuhreum). One may understand pansori as a solo opera, and aniri as a recitative.

Aniri in pansori serves specific functions. First, it drives the narrative forward by connecting different episodes of sori. In the sori (singing) parts, the performer details specific moments within the story or sing a monologue, often indulging in, much to audience’s amusement, various delicious onomatopoeias and mimetic words, which are rich in the Korean language. During aniri, the omniscient singer provides backgrounds to those moments elaborated in sori, thereby helping audiences understand the overall storyline. For example, the singer can act as a narrator and inform a change of scenery or temporal space. Or, taking on the roles of various characters, the singer may explicate their emotional states or enact dialogues. Serving sometimes as a bridge between sori episodes, aniri helps audiences place themselves in the luxuriously elaborate storytelling. Second, aniri provides a resting point for both the singer and spectators. Such a breather is necessary because a pansori performance can last hours—sometimes up to eight hours (in modern performances vocalists choose certain parts of a story).<2> A singer can rest his or her voice during aniri, while the shifts between rhythmless aniri and rhythmic sori helps refresh the attention of the spectators.

An interesting connection can be made between the role of aniri in pansori and that of the pitch center in the first movement of the Cello Concerto. Each of the three movements of the Cello Concertois organized around a single pitch center, with another pitch of secondary importance. (Chin has previously employed a similar strategy in her vocal chamber work Akrostichon-Wortspiel). In the first movement, the pitch center is G#, and the secondary pitch is Bb. The pitch centrality is apparent from very beginning: G# is the first sound of the movement, ringing mysteriously in the harps and then reinforced by the orchestra through the rest of the movement. The G# is also often the starting and ending points of the solo cello parts as well as a marker of change in texture.

Above all, the pitch center serves as a seed from which musical energy germinates. Take, for instance, the beginning of the movement. The harp plays G# with pizzicato; the cello adds a layer by momentarily playing Bb, the secondary pitch, and then converges onto G#. Soon join the percussion and the double bass, which plays G#2 in harmonics to create shimmering, ethereal timbre that is characteristic of Chin’s music. The layers of sound centering around the pitch center form the ground from which the cello can soar and plunge into an abyss. Also, the anchoring pitch, reverberating warmly and mysteriously, creates room for the cello to revel in the magic of different musical moments—just as a pansori singer can relish the details of memorable moments of a plot during sori because aniri provides the backbone of the storyline.

As mentioned, the pitch center appears in between different musical episodes, each defined by distinct texture, rhythm, or tempi. Much as aniri connects various sori sections, the pitch center is the bridge of each transition in the Cello Concerto. Tracing the recurring pedal on G# reveals the form of the movement, which can be understood as vaguely following sonata form: an introduction of the central idea, development, (cadenza), and a restatement of that idea. Here, the central idea is the pitch center that is only minimally “developed” in the first two statements (up to measure 40). And then, through five different episodes, the music explores distant places; after each excursion the G# returns, reminding listeners that that is where we began and where we ought to return. (Ironically, the movement ends with a dissolution of that central pitch: after a lengthy drone on G#, the cello line free-falls through a long glissando, then the entire orchestra explodes, playing sfffffz, against which the cello plays a semi-aleatoric passage. The effect is like countless shimmering starlets after a big bang; the movement ends in pppppp.)

Despite similarities with traditional sonata form, there is an important distinction: the pitch center of the Cello Concerto remains unchanged and returns regularly, and a sense of development is conveyed mainly through an increasing intensity of each episode. There is no departure from or recovery of the “home pitch.” Such regular recurrence of a single pitch echoes a certain linear quality of Korean traditional music, which is driven melodically and rhythmically, rather than by the logic of harmonic progression. Also, the sequential arrangement of each section of the first movement of the Cello Concerto resembles the alternation between sori and aniri of pansori. In both cases, because of this linear structure, there is a sense of openness that almost seems to allow flexibility of the length of a performance (in fact, a pansori performance can be lengthened or shortened extemporaneously).

Finally, thinking of the Cello Concerto and its use of the pitch center in connection to pansori, we may imagine that, maybe, Chin conceived the work as a sort of a story. But even if that was the case, we won’t know what the story is, because Chin is often not keen on revealing her stories. She likes her audiences to imagine. Even in her vocal works, she intentionally creates texts that are not meant to be understood, but rather are intended to be experienced, so we should “not try to understand.” (This was her explicit request to the audience at one performance of her Akrostichon-Wortspiel.)<3> Often drawing from multiple cultures in a single work—as she did in Kalá (2000; uses literary works in German, French, Danish, Finnish and Latin), Miroirs des temps (2001; employs a Portuguese poem and Ciconia’s works),<4> or Cantatrix Sopranica (2005; draws from American and German literature, and a song from the Tang dynasty)<5>—she avoids attaching specific messages to the texts. This tendency may also arise from her Bhabha-esque belief in the untenability of the notion of “pure” culture. “Cultures evolve through the process of exchanges and interlaces,” she notes. “I think that no society has an absolutely pure, uninfluenced cultural root.”<6> Chin’s uncontextualized use of the term aniri, given without an explanation of what it is or how it is used in the Cello Concerto, evokes our imagination. Her terse hint opens the door to multiple imaginative readings, one of which is explored here.

***<1>Unsuk Chin, “Akrostichon-Wortspiel. Sieben Szenen aus Märchen für Sopran und Ensemble (1991–1993)” [Acrostic Wordplay, “Seven scenes from fairy-tales for soprano and ensemble (1991–1993)”], in Im Spiegel der Zeit: Die Komponistin Unsuk Chin, ed. Stefan Drees, (Mainz: Schott, 2011), 60.

<2>Robert Koehler and Ji-yeon Byeon, Traditional Music: Sounds in Harmony with Nature, eds. Jin-hyuk Lee and Colin A. Mouat (Seoul: Korea Foundation: Seoul Selection, 2011), 56.

<3>The performance took place on November 11, 2015 in the “Beyond Darmstadt” concert by Curtis 20/21 Ensemble, of which Chin was composer-in-residence for 2015–2016. A video clip of this performance is available on YouTube: “Alize Rozsnyai, Soprano “Akrostichon Wortspiel”—Unsuk Chin,” YouTube video, 21:10, posted by “Alize Rozsnyai,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S- aZw6r2-wM (accessed 12 February 2016).

<4>See Program Note on Boosey & Hawkes’s website: “Chin, Unsuk: Miroirs des temps,” Boosey & Hawkes, last accessed February 23, 2018, http://www.boosey.com/cr/music/Unsuk-Chin-Miroirs-des-temps/5584.

<5>Chin adapts literary works by novelist Harry Mathews and German dramatist Arno Holz in this work. “Chin, Unsuk: Cantatrix Sopranica,” Boosey & Hawkes, last accessed February 23, 2018, http://www.boosey.com/cr/music/Unsuk-Chin-Cantatrix-Sopranica/45367.

<6>Unsuk Chin and Patrick Hahn, “Honjae doen jŏnchesung kwa ŏnŏ yuhhŭI” [Mixed Identity and Wordplay], in Stefan Derees, and Hŭi-kyŏng Yi, Chin Ŭn-suk, miraeŭi akporŭl kŭrit: ‘Arŭsŭ noba' Chin Ŭn-suk, hyŏndaeumakŭl ‘ŭmak’ ŭro mandŭlda [Unsuk Chin, drawing the score of the future: ‘Ars Nova’ Unsuk Chin turns contemporary music into “music”] (Mainz: Schott, 2011), 58-59. See Homi Bhabha, Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994).

***

![]() Jung-Min (Mina) Lee has recently earned her PhD from Duke University with a dissertation on Korean National Identity and Modern Music after World War II. She has taught at the Montclair State University and Baekseok Arts University in Seoul; next year, she will teach courses on Music in Modern Korea and K-pop at the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department at Duke University. Her study on Korean composer Chung Tae-bong has been published in a collection of essays by the Seoul National University Press in 2017. Current research interests include Isang Yun’s early serial music as well as the reception of Béla Bartók in South Korea in the post-WWII decade.

Jung-Min (Mina) Lee has recently earned her PhD from Duke University with a dissertation on Korean National Identity and Modern Music after World War II. She has taught at the Montclair State University and Baekseok Arts University in Seoul; next year, she will teach courses on Music in Modern Korea and K-pop at the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department at Duke University. Her study on Korean composer Chung Tae-bong has been published in a collection of essays by the Seoul National University Press in 2017. Current research interests include Isang Yun’s early serial music as well as the reception of Béla Bartók in South Korea in the post-WWII decade.

Unsuk Chin, born in South Korea and now based in Germany, has only occasionally engaged with traditional Korean or Asian music. Among a handful of examples is the last movement of Akrostichon-Wortspiel (1991), titled “Aus der alten Zeit,” described as “an ironic commentary on the traditional Korean court music” (it is left to the listeners to determine which features are based on Korean music and why they are “ironic.”)<1> She also wrote for the traditional Chinese instrument sheng in Šu for sheng and orchestra in 2009. She emphasized, however, that her motivation to write for a traditional Asian instrument was the new sound possibilities revealed in the playing of the virtuoso sheng player Wu Wei, rather than a broader interest in mixing Asian and Western music. The first movement of Chin’s Cello Concerto, written in 2008 and revised in 2013, is a rare case in which she refers to specific element of Korean traditional music, with the subtitle “Aniri.” Yet Chin has not explained what that subtitle means, or how it relates to the movement, leaving it up to listeners and performers to make their own interpretations.

Let me first introduce the term aniri, before offering a reading of how it may explain a structural aspect of the first movement of the Cello Concerto. Aniri is an element of the Korean traditional vocal genre pansori, a narrative epic drama performed by a vocalist, soriggun, and a percussionist, gosu. The vocalist tells a story through singing (sori), speech (aniri) and theatrical gestures (nuhreum). One may understand pansori as a solo opera, and aniri as a recitative.

Aniri in pansori serves specific functions. First, it drives the narrative forward by connecting different episodes of sori. In the sori (singing) parts, the performer details specific moments within the story or sing a monologue, often indulging in, much to audience’s amusement, various delicious onomatopoeias and mimetic words, which are rich in the Korean language. During aniri, the omniscient singer provides backgrounds to those moments elaborated in sori, thereby helping audiences understand the overall storyline. For example, the singer can act as a narrator and inform a change of scenery or temporal space. Or, taking on the roles of various characters, the singer may explicate their emotional states or enact dialogues. Serving sometimes as a bridge between sori episodes, aniri helps audiences place themselves in the luxuriously elaborate storytelling. Second, aniri provides a resting point for both the singer and spectators. Such a breather is necessary because a pansori performance can last hours—sometimes up to eight hours (in modern performances vocalists choose certain parts of a story).<2> A singer can rest his or her voice during aniri, while the shifts between rhythmless aniri and rhythmic sori helps refresh the attention of the spectators.

Singer Sook-sun Ahn, drummer Hwa-young Chung; the performance starts with aniri at 00:38. From Sugung-ga [Song of the underwater castle], tale of a rabbit who flees a sea king’s palace using his wit after being lured to go underwater by a turtle, a servant of the palace looking for a rabbit’s liver to use as medicine for his ailing king; the scenes in the video clip are conversations between the rabbit and the turtle (00:38-7:07) then between the rabbit and the sea king (7:11-end)

An interesting connection can be made between the role of aniri in pansori and that of the pitch center in the first movement of the Cello Concerto. Each of the three movements of the Cello Concertois organized around a single pitch center, with another pitch of secondary importance. (Chin has previously employed a similar strategy in her vocal chamber work Akrostichon-Wortspiel). In the first movement, the pitch center is G#, and the secondary pitch is Bb. The pitch centrality is apparent from very beginning: G# is the first sound of the movement, ringing mysteriously in the harps and then reinforced by the orchestra through the rest of the movement. The G# is also often the starting and ending points of the solo cello parts as well as a marker of change in texture.

Above all, the pitch center serves as a seed from which musical energy germinates. Take, for instance, the beginning of the movement. The harp plays G# with pizzicato; the cello adds a layer by momentarily playing Bb, the secondary pitch, and then converges onto G#. Soon join the percussion and the double bass, which plays G#2 in harmonics to create shimmering, ethereal timbre that is characteristic of Chin’s music. The layers of sound centering around the pitch center form the ground from which the cello can soar and plunge into an abyss. Also, the anchoring pitch, reverberating warmly and mysteriously, creates room for the cello to revel in the magic of different musical moments—just as a pansori singer can relish the details of memorable moments of a plot during sori because aniri provides the backbone of the storyline.

As mentioned, the pitch center appears in between different musical episodes, each defined by distinct texture, rhythm, or tempi. Much as aniri connects various sori sections, the pitch center is the bridge of each transition in the Cello Concerto. Tracing the recurring pedal on G# reveals the form of the movement, which can be understood as vaguely following sonata form: an introduction of the central idea, development, (cadenza), and a restatement of that idea. Here, the central idea is the pitch center that is only minimally “developed” in the first two statements (up to measure 40). And then, through five different episodes, the music explores distant places; after each excursion the G# returns, reminding listeners that that is where we began and where we ought to return. (Ironically, the movement ends with a dissolution of that central pitch: after a lengthy drone on G#, the cello line free-falls through a long glissando, then the entire orchestra explodes, playing sfffffz, against which the cello plays a semi-aleatoric passage. The effect is like countless shimmering starlets after a big bang; the movement ends in pppppp.)

Despite similarities with traditional sonata form, there is an important distinction: the pitch center of the Cello Concerto remains unchanged and returns regularly, and a sense of development is conveyed mainly through an increasing intensity of each episode. There is no departure from or recovery of the “home pitch.” Such regular recurrence of a single pitch echoes a certain linear quality of Korean traditional music, which is driven melodically and rhythmically, rather than by the logic of harmonic progression. Also, the sequential arrangement of each section of the first movement of the Cello Concerto resembles the alternation between sori and aniri of pansori. In both cases, because of this linear structure, there is a sense of openness that almost seems to allow flexibility of the length of a performance (in fact, a pansori performance can be lengthened or shortened extemporaneously).

Finally, thinking of the Cello Concerto and its use of the pitch center in connection to pansori, we may imagine that, maybe, Chin conceived the work as a sort of a story. But even if that was the case, we won’t know what the story is, because Chin is often not keen on revealing her stories. She likes her audiences to imagine. Even in her vocal works, she intentionally creates texts that are not meant to be understood, but rather are intended to be experienced, so we should “not try to understand.” (This was her explicit request to the audience at one performance of her Akrostichon-Wortspiel.)<3> Often drawing from multiple cultures in a single work—as she did in Kalá (2000; uses literary works in German, French, Danish, Finnish and Latin), Miroirs des temps (2001; employs a Portuguese poem and Ciconia’s works),<4> or Cantatrix Sopranica (2005; draws from American and German literature, and a song from the Tang dynasty)<5>—she avoids attaching specific messages to the texts. This tendency may also arise from her Bhabha-esque belief in the untenability of the notion of “pure” culture. “Cultures evolve through the process of exchanges and interlaces,” she notes. “I think that no society has an absolutely pure, uninfluenced cultural root.”<6> Chin’s uncontextualized use of the term aniri, given without an explanation of what it is or how it is used in the Cello Concerto, evokes our imagination. Her terse hint opens the door to multiple imaginative readings, one of which is explored here.

You can listen to Unsuk Chin’s Cello Concerto here:

Performed by the Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra; Alban Gerchardt, cello; Myung-whun Chung, conductor, recorded and released by Deutsche Grammophon, August 2014

***

<2>Robert Koehler and Ji-yeon Byeon, Traditional Music: Sounds in Harmony with Nature, eds. Jin-hyuk Lee and Colin A. Mouat (Seoul: Korea Foundation: Seoul Selection, 2011), 56.

<3>The performance took place on November 11, 2015 in the “Beyond Darmstadt” concert by Curtis 20/21 Ensemble, of which Chin was composer-in-residence for 2015–2016. A video clip of this performance is available on YouTube: “Alize Rozsnyai, Soprano “Akrostichon Wortspiel”—Unsuk Chin,” YouTube video, 21:10, posted by “Alize Rozsnyai,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S- aZw6r2-wM (accessed 12 February 2016).

<4>See Program Note on Boosey & Hawkes’s website: “Chin, Unsuk: Miroirs des temps,” Boosey & Hawkes, last accessed February 23, 2018, http://www.boosey.com/cr/music/Unsuk-Chin-Miroirs-des-temps/5584.

<5>Chin adapts literary works by novelist Harry Mathews and German dramatist Arno Holz in this work. “Chin, Unsuk: Cantatrix Sopranica,” Boosey & Hawkes, last accessed February 23, 2018, http://www.boosey.com/cr/music/Unsuk-Chin-Cantatrix-Sopranica/45367.

<6>Unsuk Chin and Patrick Hahn, “Honjae doen jŏnchesung kwa ŏnŏ yuhhŭI” [Mixed Identity and Wordplay], in Stefan Derees, and Hŭi-kyŏng Yi, Chin Ŭn-suk, miraeŭi akporŭl kŭrit: ‘Arŭsŭ noba' Chin Ŭn-suk, hyŏndaeumakŭl ‘ŭmak’ ŭro mandŭlda [Unsuk Chin, drawing the score of the future: ‘Ars Nova’ Unsuk Chin turns contemporary music into “music”] (Mainz: Schott, 2011), 58-59. See Homi Bhabha, Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994).

***

Jung-Min (Mina) Lee has recently earned her PhD from Duke University with a dissertation on Korean National Identity and Modern Music after World War II. She has taught at the Montclair State University and Baekseok Arts University in Seoul; next year, she will teach courses on Music in Modern Korea and K-pop at the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department at Duke University. Her study on Korean composer Chung Tae-bong has been published in a collection of essays by the Seoul National University Press in 2017. Current research interests include Isang Yun’s early serial music as well as the reception of Béla Bartók in South Korea in the post-WWII decade.

Jung-Min (Mina) Lee has recently earned her PhD from Duke University with a dissertation on Korean National Identity and Modern Music after World War II. She has taught at the Montclair State University and Baekseok Arts University in Seoul; next year, she will teach courses on Music in Modern Korea and K-pop at the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department at Duke University. Her study on Korean composer Chung Tae-bong has been published in a collection of essays by the Seoul National University Press in 2017. Current research interests include Isang Yun’s early serial music as well as the reception of Béla Bartók in South Korea in the post-WWII decade.

↧

The Sound of Empathy in George Lewis’s Afterword

By Alexander K. Rothe

Premiered in 2015 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Afterword is a two-act opera composed by George Lewis to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). I approach the opera as an opportunity to examine the role of community and empathy in Lewis’s works. Though Lewis discusses empathy in terms of a specific community—the AACM on the South Side of Chicago—I apply his thinking to the role of the listener in general. Lewis’s musical works, especially Afterword, demonstrate the sound of empathy—the sound of pushing existing boundaries while at the same time calling on the active participation of the listener as a creative improviser.

(Afterword, Act 1, scene 4, from left to right: Julian Terrell Otis, Gwendolyn Brown, and Joelle Lamarre. Photo by George Lewis)

In a recent interview, George Lewis describes his conception of community and empathy in Afterword:

At the AACM’s first meeting in May 1965, musicians gathered to discuss how they could survive in an environment where black musicians were being pushed out of the South Side of Chicago. Confronted with an exploitative music industry and a city council that sought to shut down music venues on the South Side, the musicians voted to form an organization for the promotion of creative music—original music outside the restrictive genre markers of the music industry.

A key aspect of the AACM from its inception, genre mobility refers to transcending the existing musical system and its genre boundaries, drawing on a broad range of different musical languages. Through genre mobility, AACM members were able to resist restrictive genre markers while exploring new networks and infrastructural pathways.

As described by Lewis in his 2008 book, A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music, in the early days of the AACM, empathy was especially evident in Muhal Richard Abrams’s aim of “awakening the psyche” of his fellow creative musicians. On the one hand, this was a commitment to original music and the need to be supportive of fellow creative musicians. On the other, it involved concern for the “spiritual growth” of the community—to provide free education for young musicians and present imaginative programs of creative music to the public.

The Sound of Empathy and Genre Mobility

Drawing on the scholarship of Suzanne Keen, I interpret empathy as a shared experience and feeling. Keen discusses empathy as including two aspects: it is a spontaneously shared emotion that also involves cognitive perspective taking.<2> This perspective taking is always shaped by cultural and individual factors of memory and experience. In a chapter on empathy, improvisation, and embodied cognition, Vijay Iyer likewise stresses how our perception of others is grounded in a culturally-situated understanding of embodied action.<3> According to Iyer, empathy is a kind of action understanding that activates similar motor programs in the observer’s brain when experiencing music—i.e. bodies in motion.

Ryan Dohoney’s research on Julius Eastman has been instrumental in shaping my thinking about empathy in terms of genre mobility. In a chapter on Julius Eastman’s life and music in New York City in the period between 1976 and 1990, Dohoney examines how Eastman was able to connect diverse networks at venues such as The Kitchen, Environ, and Paradise Garage.<4> During this period, Eastman composed and performed music that defies a single genre label—mixing extended vocal techniques, experimental music, improvisation, and disco.

George Lewis’s music demonstrates a similar sort of empathy through genre mobility and drawing on multiple networks. In Lewis’s music, the sound of empathy is of pushing existing boundaries, giving rise to a feeling of instability that calls for the active participation of the listener as a creative improviser. In the process of doing so, it activates the desire for change in everyday life.

(Afterword, Act 1, scene 4, 1:45:44-1:58:19; Ojai Music Festival performance, June 9, 2017, Libbey Bowl, Ojai, CA)

The sound of empathy is especially evident in scene 4 of Afterword, entitled “First Meeting.” Based on Lewis’s transcript of an audio recording of the founding AACM meeting in May 1965, this scene depicts the musicians in the process of deciding to perform only original music. As the musicians discuss various types of music, Lewis uses the opportunity to compose music that comments on music (music about music)—a tradition that stretches back to Monteverdi’s Orfeo.

A close listening of this scene reveals that there is no over-arching global form. Instead, Lewis works with modules—approximately ten to fifteen measures of music at a time—which he brings back, but changes with each repetition. The layering of ostinatos and sustained chords results in a thick, complex sound. Lewis creates a shared feeling of instability by means of jump cuts between sections and extended techniques that destabilize pitch (e.g., glissando, microtonal inflection, tremolo). In the vocal writing, he contrasts recitative-like passages, which are unmetered and occur over sustained chords, with metered arioso passages. Lewis stresses the clarity of the text through syllabic treatment.

A key technique of genre mobility is musical signifyin(g), a practice of quoting or referring to preexisting material that in turn changes it by adding a new layer of meaning—whether playful, subversive, or as a means of paying tribute to someone or something (on musical signifyin(g), see Samuel Floyd).<5> Afterword’s scene 4 includes a number of examples of musical signifyin(g). When soprano Joelle Lamarre’s avatar sings “we thought of all the things we are,” the music references the jazz standard “All the Things You Are” (1:47:07). Given that the AACM members rejected the genre marker of jazz, this reference is a playful subversion of existing genre boundaries. When the text alludes to music on the radio (“The other music is already being presented; record companies, disk jockeys, everyone is promoting it”), Lewis signifies on the groove-oriented nature of much popular black music in the mid-1960s (funk and R&B; 1:51:38). Lastly, whenever the text refers to original or creative music (1:48:19, 1:50:01, 1:54:16, 1:56:51), Lewis layers multiple loops on top of each other. He is signifyin(g) on the idea of creative music as involving the complex layering of sounds. In sum, we encounter a sense of empathy through the shared feeling of instability along with the shared experience of Lewis pushing existing genre boundaries.

The Improvising Listener

The absence of a global form, the complex layering of loops, and stark contrasts of sound—these are all techniques that call on the active participation of the listener as a creative improviser. While Afterword’s score is fully notated—i.e. there is no improvisation at the level of the performers—this does not exclude the possibility of the improvising listener. Lewis writes of the listener:

In other words, the listener participates in the performance as an improviser, which is akin to the experience of improvisation in everyday life. In Afterword’s scene 4, the improvising listener navigates multiple layers of sound and creates a pathway through disparate blocks of sound. The fact that the singers’ text always remains in the foreground in no way diminishes the role of the listener as creative improviser. By experiencing this scene in the context of a musical language of instability, we have all the more appreciation for the difficult task confronted by AACM musicians at the first meeting. While the listener to some degree self-identifies with the AACM musicians, empathetic listening in this case refers more broadly to the shared feeling of instability and pushing existing boundaries.

In recent years, empathy—as a mode of emotionally engaging with music and literature—has received much criticism. Molly Abel Travis argues for the necessity of moving beyond the self-identification of empathy, instead adopting an attitude of openness to experiences of difference that “interrupt our epistemological projects to contain the other.”<7> However, it is exactly this attitude of openness that Lewis’s opera fosters by pushing existing genre boundaries. In doing so, he creates a shared feeling of instability that simultaneously activates the listener’s own mobility as a creative improviser. As listeners to Afterword, we encounter a model for thinking about improvisation in everyday life, seeking similar experiences of pushing boundaries of social injustice.

***

<1>Lewis quoted in Alexander K. Rothe, “An Interview with the Composer,” VAN Magazine June 22, 2017.

<2>Suzanne Keen, Empathy and the Novel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 4 & 27.

<3>Vijay Iyer, “Improvisation, Action Understanding, and Music Cognition with and without Bodies,” in The Oxford Handbook of Critical Improvisation Studies, Volume 1, ed. George E. Lewis and Benjamin Piekut (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 81.

<4>Ryan Dohoney, “A Flexible Musical Identity: Julius Eastman in New York City, 1976-90,” in Gay Guerrilla: Julius Eastman and His Music, ed. Renée Levine Packer and Mary Jane Leach (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2015). See especially 126f.

<5>Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., “African-American Modernism, Signifyin(g), and Black Music,” in The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History from Africa to the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 87-99.

<6>George E. Lewis, “Mobilitas Animi: Improvising Technologies, Intending Chance,” Parallax 13, no. 4 (2007): 113.

<7>Molly Abel Travis, “Beyond Empathy: Narrative Distancing and Ethics in Toni Morrison’s Beloved and J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace,” Journal of Narrative Theory 40, no. 2 (Summer 2010): 232.

***

![]()

Alexander K. Rothe is a Core Lecturer at Columbia University, where he completed his PhD in Historical Musicology in 2015. His interests are opera staging, Regieoper, Wagner Studies, and new music. He is currently working on a book project on stagings of Wagner’s Ring cycle and afterlives of 1968 in divided Germany. His research has been published by Musical Quarterly and Tempo, and he has received research grants from the Fulbright Program and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

Premiered in 2015 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Afterword is a two-act opera composed by George Lewis to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). I approach the opera as an opportunity to examine the role of community and empathy in Lewis’s works. Though Lewis discusses empathy in terms of a specific community—the AACM on the South Side of Chicago—I apply his thinking to the role of the listener in general. Lewis’s musical works, especially Afterword, demonstrate the sound of empathy—the sound of pushing existing boundaries while at the same time calling on the active participation of the listener as a creative improviser.

(Afterword, Act 1, scene 4, from left to right: Julian Terrell Otis, Gwendolyn Brown, and Joelle Lamarre. Photo by George Lewis)

In a recent interview, George Lewis describes his conception of community and empathy in Afterword:

Community is essential to the opera’s themes. What we’re seeing is a community in formation. People are coming together to find commonalities, and they need to come together because nobody is really supporting them. […] And we’re seeing the stresses and strains of community formation—disagreements of different kinds. But at the same time there is a need to forge a community that is accepting of different points of view. This is when you get to the empathy part. Empathy is also fundamental to the creation of this community; we need empathy to establish community. People need to be receptive and open. They need to even make themselves a little vulnerable, and we see this in the opera as well. There is a sense in which people aren’t sure what’s going to happen.<1>

At the AACM’s first meeting in May 1965, musicians gathered to discuss how they could survive in an environment where black musicians were being pushed out of the South Side of Chicago. Confronted with an exploitative music industry and a city council that sought to shut down music venues on the South Side, the musicians voted to form an organization for the promotion of creative music—original music outside the restrictive genre markers of the music industry.

A key aspect of the AACM from its inception, genre mobility refers to transcending the existing musical system and its genre boundaries, drawing on a broad range of different musical languages. Through genre mobility, AACM members were able to resist restrictive genre markers while exploring new networks and infrastructural pathways.

As described by Lewis in his 2008 book, A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music, in the early days of the AACM, empathy was especially evident in Muhal Richard Abrams’s aim of “awakening the psyche” of his fellow creative musicians. On the one hand, this was a commitment to original music and the need to be supportive of fellow creative musicians. On the other, it involved concern for the “spiritual growth” of the community—to provide free education for young musicians and present imaginative programs of creative music to the public.

The Sound of Empathy and Genre Mobility

Drawing on the scholarship of Suzanne Keen, I interpret empathy as a shared experience and feeling. Keen discusses empathy as including two aspects: it is a spontaneously shared emotion that also involves cognitive perspective taking.<2> This perspective taking is always shaped by cultural and individual factors of memory and experience. In a chapter on empathy, improvisation, and embodied cognition, Vijay Iyer likewise stresses how our perception of others is grounded in a culturally-situated understanding of embodied action.<3> According to Iyer, empathy is a kind of action understanding that activates similar motor programs in the observer’s brain when experiencing music—i.e. bodies in motion.

Ryan Dohoney’s research on Julius Eastman has been instrumental in shaping my thinking about empathy in terms of genre mobility. In a chapter on Julius Eastman’s life and music in New York City in the period between 1976 and 1990, Dohoney examines how Eastman was able to connect diverse networks at venues such as The Kitchen, Environ, and Paradise Garage.<4> During this period, Eastman composed and performed music that defies a single genre label—mixing extended vocal techniques, experimental music, improvisation, and disco.

George Lewis’s music demonstrates a similar sort of empathy through genre mobility and drawing on multiple networks. In Lewis’s music, the sound of empathy is of pushing existing boundaries, giving rise to a feeling of instability that calls for the active participation of the listener as a creative improviser. In the process of doing so, it activates the desire for change in everyday life.

(Afterword, Act 1, scene 4, 1:45:44-1:58:19; Ojai Music Festival performance, June 9, 2017, Libbey Bowl, Ojai, CA)

The sound of empathy is especially evident in scene 4 of Afterword, entitled “First Meeting.” Based on Lewis’s transcript of an audio recording of the founding AACM meeting in May 1965, this scene depicts the musicians in the process of deciding to perform only original music. As the musicians discuss various types of music, Lewis uses the opportunity to compose music that comments on music (music about music)—a tradition that stretches back to Monteverdi’s Orfeo.

A close listening of this scene reveals that there is no over-arching global form. Instead, Lewis works with modules—approximately ten to fifteen measures of music at a time—which he brings back, but changes with each repetition. The layering of ostinatos and sustained chords results in a thick, complex sound. Lewis creates a shared feeling of instability by means of jump cuts between sections and extended techniques that destabilize pitch (e.g., glissando, microtonal inflection, tremolo). In the vocal writing, he contrasts recitative-like passages, which are unmetered and occur over sustained chords, with metered arioso passages. Lewis stresses the clarity of the text through syllabic treatment.

A key technique of genre mobility is musical signifyin(g), a practice of quoting or referring to preexisting material that in turn changes it by adding a new layer of meaning—whether playful, subversive, or as a means of paying tribute to someone or something (on musical signifyin(g), see Samuel Floyd).<5> Afterword’s scene 4 includes a number of examples of musical signifyin(g). When soprano Joelle Lamarre’s avatar sings “we thought of all the things we are,” the music references the jazz standard “All the Things You Are” (1:47:07). Given that the AACM members rejected the genre marker of jazz, this reference is a playful subversion of existing genre boundaries. When the text alludes to music on the radio (“The other music is already being presented; record companies, disk jockeys, everyone is promoting it”), Lewis signifies on the groove-oriented nature of much popular black music in the mid-1960s (funk and R&B; 1:51:38). Lastly, whenever the text refers to original or creative music (1:48:19, 1:50:01, 1:54:16, 1:56:51), Lewis layers multiple loops on top of each other. He is signifyin(g) on the idea of creative music as involving the complex layering of sounds. In sum, we encounter a sense of empathy through the shared feeling of instability along with the shared experience of Lewis pushing existing genre boundaries.

The Improvising Listener

The absence of a global form, the complex layering of loops, and stark contrasts of sound—these are all techniques that call on the active participation of the listener as a creative improviser. While Afterword’s score is fully notated—i.e. there is no improvisation at the level of the performers—this does not exclude the possibility of the improvising listener. Lewis writes of the listener:

[...] We can understand the experience of listening to music as very close to the experience of the improviser. Listening itself, an improvisative act engaged in by everyone, announces a practice of active engagement with the world, where we sift, interpret, store, and forget, in parallel with action and fundamentally articulated with it.<6>

In other words, the listener participates in the performance as an improviser, which is akin to the experience of improvisation in everyday life. In Afterword’s scene 4, the improvising listener navigates multiple layers of sound and creates a pathway through disparate blocks of sound. The fact that the singers’ text always remains in the foreground in no way diminishes the role of the listener as creative improviser. By experiencing this scene in the context of a musical language of instability, we have all the more appreciation for the difficult task confronted by AACM musicians at the first meeting. While the listener to some degree self-identifies with the AACM musicians, empathetic listening in this case refers more broadly to the shared feeling of instability and pushing existing boundaries.

In recent years, empathy—as a mode of emotionally engaging with music and literature—has received much criticism. Molly Abel Travis argues for the necessity of moving beyond the self-identification of empathy, instead adopting an attitude of openness to experiences of difference that “interrupt our epistemological projects to contain the other.”<7> However, it is exactly this attitude of openness that Lewis’s opera fosters by pushing existing genre boundaries. In doing so, he creates a shared feeling of instability that simultaneously activates the listener’s own mobility as a creative improviser. As listeners to Afterword, we encounter a model for thinking about improvisation in everyday life, seeking similar experiences of pushing boundaries of social injustice.

***

<1>Lewis quoted in Alexander K. Rothe, “An Interview with the Composer,” VAN Magazine June 22, 2017.

<2>Suzanne Keen, Empathy and the Novel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 4 & 27.

<3>Vijay Iyer, “Improvisation, Action Understanding, and Music Cognition with and without Bodies,” in The Oxford Handbook of Critical Improvisation Studies, Volume 1, ed. George E. Lewis and Benjamin Piekut (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 81.

<4>Ryan Dohoney, “A Flexible Musical Identity: Julius Eastman in New York City, 1976-90,” in Gay Guerrilla: Julius Eastman and His Music, ed. Renée Levine Packer and Mary Jane Leach (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2015). See especially 126f.

<5>Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., “African-American Modernism, Signifyin(g), and Black Music,” in The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History from Africa to the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 87-99.

<6>George E. Lewis, “Mobilitas Animi: Improvising Technologies, Intending Chance,” Parallax 13, no. 4 (2007): 113.

<7>Molly Abel Travis, “Beyond Empathy: Narrative Distancing and Ethics in Toni Morrison’s Beloved and J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace,” Journal of Narrative Theory 40, no. 2 (Summer 2010): 232.

***

Alexander K. Rothe is a Core Lecturer at Columbia University, where he completed his PhD in Historical Musicology in 2015. His interests are opera staging, Regieoper, Wagner Studies, and new music. He is currently working on a book project on stagings of Wagner’s Ring cycle and afterlives of 1968 in divided Germany. His research has been published by Musical Quarterly and Tempo, and he has received research grants from the Fulbright Program and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

↧

"Will we remember the way we were?" The past and future tenses of Lauryn Hill's "Ex-Factor"

By Lauren Eldridge

Beyond the coterminous release of "Nice for What" and "Be Careful," there is much to think through in regards to the past and future tenses of "Ex-Factor," a single from Hill's 1998 album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.<1> "Ex-Factor" itself is the product of a sample of a sample of a cover. Hill's opening verse - "It could all be so simple" - draws on "Can It Be All So Simple" by the Wu-Tang Clan (1993), which in turn samples Gladys Knight's voice in "The Way We Were" (1974), a cover of the same song by Barbra Streisand (1973). The first few moments of "Ex-Factor" are reminiscent of "Lovin' You" by Minnie Riperton (1974), with instrumentation that resembles acoustic piano and guitar, respectively, and chirping birds. This evocation of 1970's soul music, an intentional nostalgia meant to signal a dreamscape, serves to establish a sonic framework for the unrequited affection of the singer; the listener is meant to understand that this story will not end well. The specific callback to Riperton is in sharp contrast with the rest of the album, which combines such disparate sonic forces as the record scratches on "Lost Ones" and the gentle finger snaps on "Nothing Even Matters." Yet, each of these elements have the effect of invoking a sense of place, whether that scene is a street rap battle (Lost Ones) or a café ballad (Nothing Even Matters).

Though the beginning of "Ex-Factor" pulls from the past, it is the song's hook that is sampled by Drake and Cardi B. "Be Careful" plays with the word "care," eliding the refrain "be careful with me" with "care for me," resulting in the polysemic "be careful with, care for me, always said that you'd be there for me, there for me." The subject matter aligns closely with that of "Ex-Factor"; once again, the listener should not hold their breath for a happy ending. In stark contrast, "Nice for What" is ebullient in nature, praising its subject matter. The rapper (Drake) rebukes the singer (Hill) as she confesses "I keep letting you back in; how can I explain myself?" In this song, "care for me" becomes an incessant backdrop reinforcing the unnecessary nature of concern. Broken promises, intoned over and over again, lock together in a dance floor to which the listener is called by the emcee. But who is this emcee, especially in a song that samples from a subgenre of hip hop dependent on the right voice to get the party started?

"Nice for What" is an interpretation of bounce music from the North American Gulf South region. As a genre, bounce can be distinguished by its particular use of samples - extremely short sound clips are looped together to create a tapestry of danceable music. This music is then mixed and remade in live performance. Because a great deal of importance is placed on live performance, songs may have two subjects: one that can be grasped through the lyrics, and the other following the command of the master of ceremonies. After listening to a few moments of "Nice for What," it becomes clear that the dance caller isn't actually Drake, but another's voice at a remove, reproduced in lower definition. The sampled figure arguably more present than the spectral timbre of Lauryn Hill's nostalgia is bounce musician Big Freedia.<2> Her voice is frequently instrumentalized, mechanized, and compartmentalized into ever-reducing fragments of phrases that build new thoughts, new jokes, and new insights (see, for example, the descending chromatic scale that introduces the "Queen Diva" on the track "Explode" from Just Be Free).

At about 2' 07", Big Freedia interjects Drake's isolating call and response with a call and response of her own that literally crackles with liveness. The track abruptly shifts from a blend of smoothly constructed studio voices to Big Freedia calling on a microphone with feedback and an audience screaming in response. Drake does manage to signify on the verbosity of bounce music, a verbal density that results from multiple levels of sampling. Now "watch the breakdown": the track reduces all the way down to the Hill sample to rebuild over the next thirty seconds or so into its most recognizable bounce state. In order to fulfill the requisites of the genre, Drake himself is sampled, cutting and mixing earlier sing-song fragments into the 3-3-2 rhythm that undergirds the bounce.

Gladys Knight begins her version of "The Way We Were" (and the Wu Tang Clan's) by asserting that "everybody's talking about the good old days," but continues to wonder at the inevitability of the passage of time, and that future people, perhaps even her descendants would refer to her turbulent present reality as the "good old days."Lauryn Hill has noted the significance of her song being sampled in live performance, thus elevating it to the level of a "classic." These examples demonstrate the power of music legacy, in that sampling provides the opportunity to hear simultaneously "the way we were" and also what we might become.

***

<1>This year marks the 20th year anniversary of this celebrated album's release, for which Hill has planned a 26-city tour.

<2>Though beyond the scope of this piece, Big Freedia is a major national representative of this otherwise regional genre. Helpful resources in understanding her media reception can be found in the writing of Myles Johnson for Vice and Ben Dandridge-Lemco for the Fader.

***

![]() Lauren Eldridge is an administrator and lecturer at Spelman College. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in Music in 2016, and usually writes about classical music in Haiti.

Lauren Eldridge is an administrator and lecturer at Spelman College. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in Music in 2016, and usually writes about classical music in Haiti.

"Care for me, care for me, you said you care for meThis couplet serves as the foundation for both the songs at #1 and #9 on the Apple Music charts as of Friday, April 13, 2018 by two artists listed several times on the Billboard Hot 100. Drake's "Nice for What" and Cardi B's "Be Careful" both sample "Ex-Factor" by Lauryn Hill (1998). By reading sampling as a vital creative process, these three songs become links in a chain connecting four decades of black American music.

There for me, there for me, said you'd be there for me"

Beyond the coterminous release of "Nice for What" and "Be Careful," there is much to think through in regards to the past and future tenses of "Ex-Factor," a single from Hill's 1998 album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.<1> "Ex-Factor" itself is the product of a sample of a sample of a cover. Hill's opening verse - "It could all be so simple" - draws on "Can It Be All So Simple" by the Wu-Tang Clan (1993), which in turn samples Gladys Knight's voice in "The Way We Were" (1974), a cover of the same song by Barbra Streisand (1973). The first few moments of "Ex-Factor" are reminiscent of "Lovin' You" by Minnie Riperton (1974), with instrumentation that resembles acoustic piano and guitar, respectively, and chirping birds. This evocation of 1970's soul music, an intentional nostalgia meant to signal a dreamscape, serves to establish a sonic framework for the unrequited affection of the singer; the listener is meant to understand that this story will not end well. The specific callback to Riperton is in sharp contrast with the rest of the album, which combines such disparate sonic forces as the record scratches on "Lost Ones" and the gentle finger snaps on "Nothing Even Matters." Yet, each of these elements have the effect of invoking a sense of place, whether that scene is a street rap battle (Lost Ones) or a café ballad (Nothing Even Matters).

Though the beginning of "Ex-Factor" pulls from the past, it is the song's hook that is sampled by Drake and Cardi B. "Be Careful" plays with the word "care," eliding the refrain "be careful with me" with "care for me," resulting in the polysemic "be careful with, care for me, always said that you'd be there for me, there for me." The subject matter aligns closely with that of "Ex-Factor"; once again, the listener should not hold their breath for a happy ending. In stark contrast, "Nice for What" is ebullient in nature, praising its subject matter. The rapper (Drake) rebukes the singer (Hill) as she confesses "I keep letting you back in; how can I explain myself?" In this song, "care for me" becomes an incessant backdrop reinforcing the unnecessary nature of concern. Broken promises, intoned over and over again, lock together in a dance floor to which the listener is called by the emcee. But who is this emcee, especially in a song that samples from a subgenre of hip hop dependent on the right voice to get the party started?

"Nice for What" is an interpretation of bounce music from the North American Gulf South region. As a genre, bounce can be distinguished by its particular use of samples - extremely short sound clips are looped together to create a tapestry of danceable music. This music is then mixed and remade in live performance. Because a great deal of importance is placed on live performance, songs may have two subjects: one that can be grasped through the lyrics, and the other following the command of the master of ceremonies. After listening to a few moments of "Nice for What," it becomes clear that the dance caller isn't actually Drake, but another's voice at a remove, reproduced in lower definition. The sampled figure arguably more present than the spectral timbre of Lauryn Hill's nostalgia is bounce musician Big Freedia.<2> Her voice is frequently instrumentalized, mechanized, and compartmentalized into ever-reducing fragments of phrases that build new thoughts, new jokes, and new insights (see, for example, the descending chromatic scale that introduces the "Queen Diva" on the track "Explode" from Just Be Free).

At about 2' 07", Big Freedia interjects Drake's isolating call and response with a call and response of her own that literally crackles with liveness. The track abruptly shifts from a blend of smoothly constructed studio voices to Big Freedia calling on a microphone with feedback and an audience screaming in response. Drake does manage to signify on the verbosity of bounce music, a verbal density that results from multiple levels of sampling. Now "watch the breakdown": the track reduces all the way down to the Hill sample to rebuild over the next thirty seconds or so into its most recognizable bounce state. In order to fulfill the requisites of the genre, Drake himself is sampled, cutting and mixing earlier sing-song fragments into the 3-3-2 rhythm that undergirds the bounce.

Gladys Knight begins her version of "The Way We Were" (and the Wu Tang Clan's) by asserting that "everybody's talking about the good old days," but continues to wonder at the inevitability of the passage of time, and that future people, perhaps even her descendants would refer to her turbulent present reality as the "good old days."Lauryn Hill has noted the significance of her song being sampled in live performance, thus elevating it to the level of a "classic." These examples demonstrate the power of music legacy, in that sampling provides the opportunity to hear simultaneously "the way we were" and also what we might become.

***

<1>This year marks the 20th year anniversary of this celebrated album's release, for which Hill has planned a 26-city tour.

<2>Though beyond the scope of this piece, Big Freedia is a major national representative of this otherwise regional genre. Helpful resources in understanding her media reception can be found in the writing of Myles Johnson for Vice and Ben Dandridge-Lemco for the Fader.

***

Lauren Eldridge is an administrator and lecturer at Spelman College. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in Music in 2016, and usually writes about classical music in Haiti.