by Charles T. Downey

The Metropolitan Opera and its General Manager, Peter Gelb, took a considerable risk by planning to mount John Adams's The Death of Klinghofferthis coming fall. The furor generated by the work's U.S. premiere in 1991 convinced its librettist, Alice Goodman, that it was time to stop writing opera librettos. As expected, the Anti-Defamation League and other Jewish groups have continued their objections, pressuring the Met to withdraw its production. Gelb instead offered the compromise of going ahead with the production but canceling the HD simulcast, planned for November 15, when audiences in movie theaters around the world could have seen the final performance of the run.

For many opera fans who have never had the chance to see Klinghoffer live, myself included, the decision was disappointing. Even Gelb and Abraham Foxman, the national director of the ADL, admit that the opera is not anti-Semitic, but they fear that the opera might fan anti-Semitic sentiment in some countries. Robert Fink, in a systematic and thorough 2005 article (“Klinghoffer in Brooklyn Heights,” in Cambridge Opera Journal), focused especially on the portrayal of Jewish characters in Klinghoffer, putting to rest the idea that they are anti-Semitic caricatures. On the other hand, the Palestinian characters, few would argue, are grotesquely anti-Semitic and spout the rhetoric of hate: versions of the actual terrorists who perpetrated the cold-blooded murder of Leon Klinghoffer, an American tourist in a wheelchair, during their hijacking of the Achille Lauro in 1985. The opening night of the Met's production of the opera will coincide almost exactly with the anniversary of the date on which Klinghoffer's body was brought back to the United States.

|

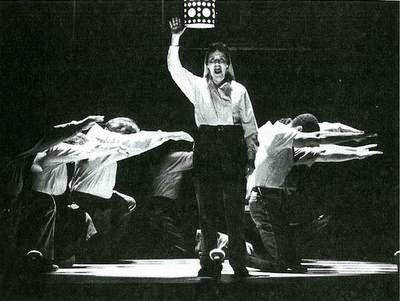

| Stephanie Friedman, mezzo-soprano, in the teenaged terrorist Omar's act II aria (1991) |

This is the real problem with The Death of Klinghoffer, pointed out in Richard Taruskin's trenchant analysis (“Music's Dangers And The Case For Control,” December 9, 2001) in the New York Times in the wake of the 9/11 attacks: “The Death of Klinghoffer trades in the tritest undergraduate fantasies. If the events of Sept. 11 could not jar some artists and critics out of their habit of romantically idealizing criminals, then nothing will.” Sadly, Taruskin was right. Is it really that difficult to understand how some people could be offended by the contextualization of Klinghoffer's murder within the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, even if only in the minds of his killers? In the same way, some people would be offended if an opera about the kidnapping of girls in Nigeria opened with a chorus laying out the political and religious grievances of the Boko Haram militants, or if an opera about the murder of journalist Daniel Pearl opened with the history of the causes behind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed's hatred of the United States.

Yet art can, and sometimes should, offend. It can make you angry and pose uncomfortable questions. Gelb's miscalculation in making this compromise was not to understand what every impresario at least since Sergei Diaghilev should know: scandal sells. Any staging of Klinghoffer courts controversy; not to take advantage of the full extent of that controversy, by canceling the biggest mass media exposure available to the Met, shows a lack of savvy. (Klinghoffer was commissioned for Brussels, after all, by the modern-day master of the succès de scandale, Gerard Mortier.)

The controversy over The Death of Klinghoffer probably enjoys greater notoriety than the opera itself: as Peter G. Davis noted of the U.S. premiere in New York Magazine, it is “more fun to talk about than to watch.” Without the perpetual polemical wars fueling its fame, Klinghoffer might have faded long ago. While I would not go as far as critic Kyle Gann, who once wrote that Philip Glass's Fall of the House of Usher“is the only opera I've ever seen worse than The Death of Klinghoffer,” the opera has some pronounced dramatic weaknesses. If the winds of controversy ever still, we may be able to assess the work on its merits, or lack thereof, but it is more likely that we will always judge Klinghoffer, at least partially, by the outrages it has provoked.

Should the Met have canceled the simulcast of The Death of Klinghoffer? No. At the same time, the chorus of hysterical reaction to the decision has reached the point of self-parody. “A chilling precedent [of] self-censorship,” fumes John van Rhein in the Chicago Tribune. “A dismaying artistic cave-in,” Anthony Tommasini writes in the New York Times. “The only anti-Semitism this work ... has ever engendered,” says Mark Swed of the Los Angeles Times, “has been because of often successful pressure from Jewish groups” to ban it. Most hyperbolic of all is Robert Fink himself, in the New York Daily News, claiming that the Met's decision to cancel the Klinghoffer simulcast will “kill off ... American opera’s future." Goodness gracious: surely not even Peter Gelb imagined he held such power in his hands.

Charles T. Downey received his Ph.D. in musicology from the Catholic University of America. In addition to scholarly publications on Gregorian chant and French Baroque opera and court ballet, he writes freelance articles and reviews of classical music for the Washington Post and other publications. He also moderates the online magazine Ionarts, devoted to classical music and the arts in Washington, D.C.

Charles T. Downey received his Ph.D. in musicology from the Catholic University of America. In addition to scholarly publications on Gregorian chant and French Baroque opera and court ballet, he writes freelance articles and reviews of classical music for the Washington Post and other publications. He also moderates the online magazine Ionarts, devoted to classical music and the arts in Washington, D.C.