By Natasha Roule

In 2015, Canal+ aired the first episode of Versailles, a Franco-Canadian television series about the young Louis XIV and his efforts to consolidate political power. As the title of the series suggests, Versailles centers its plot around the luxe chateau that the Sun King built on the site of his father’s favorite hunting lodge some 50 miles southwest of Paris. A dramatized historical fiction, the series draws from the vast historiographical literature that explores how Louis XIV cultivated his power from the seat of Versailles. Yet as the king worked to centralize the French government, he had to contend with a large kingdom beyond Versailles – a kingdom characterized by political and cultural heterogeneity that occasionally posed challenges to the king’s absolutist measures. Indeed, the political centralization of France under Louis XIV was a tricky affair: far from simply demanding that legislature be put into effect in each province, the king and his ministers engaged in a game of compromise, negotiation, and sometimes coercion with city magistrates and provincial governors. Though the history of absolutism in French cities has received some study by historians, we can gain a deeper understanding of the implementation and reception of absolutism in provincial France by approaching the subject from a musicological perspective.<1> To do this, the tragédie en musique– the absolutist genre par excellence– is key.

In my dissertation, “The Operas of Jean-Baptiste Lully and the Negotiation of Absolutism in the French Provinces, 1685-1750,” I explore the performance history of Lully’s tragédies en musique in four French cities: Marseille, Lyon, Rennes, and Strasbourg. I argue that productions of Lully’s operas in these cities played a major role in the expansion of absolutism even as they functioned as mouthpieces of provincial pushback against the Crown. On the one hand, Lully’s tragédies acted as vehicles of absolutist propaganda, lending mobility to the king’s image as an absolutist monarch in much the same way as the equestrian statues of Louis XIV that were erected in major cities throughout France.<2> At the same time, many provincial artists altered or satirized Lully’s tragédies, deliberately keying their modifications to critique royal intervention in local affairs.

Musicologists have long acknowledged the political bent of Lully’s operas. Lully (1632-1687) was the surintendant de la musique of Louis XIV and is credited with the invention of French opera, along with his librettist Philippe Quinault. With the king as his patron, the Italian-born composer ensured that references to Louis XIV and his sovereignty were woven throughout his own tragédies, from heroes who preach the importance of duty to choruses that explicitly applaud the monarch.<3> During his lifetime, Lully held a monopoly over the performance of opera that effectively restricted opera production to Paris and the court, where Lully worked.<4> It was not until after Lully’s death in 1687 that theaters across the kingdom began to produce opera, with the exception of the Académie de Musique of Marseille, which was founded with Lully’s permission in 1684. Even after opera spread to the provinces, few works besides Lully’s tragédies were performed until about 1700, a testimony to the composer’s enduring command over the French musical landscape.<5>

Marseille, Lyon, Rennes, and Strasbourg had unique cultural, linguistic, and political profiles that shaped local responses to Lully’s operas. In Marseille, Pierre Gautier, founder of the Marseille Académie de Musique, composed two operas modeled after Lully’s tragédies that asserted the city’s simultaneous loyalty to the absolutist Crown as well as its adherence to its historically civic republican identity.<6> In Lyon, parodies of Lully’s operas performed in the 1690s coincided with the city’s struggle to recover from famine and contagion without significant aid from the Crown. In a parody of Lully’s Phaëton, the character of a Lyonnais municipal sergeant replaces that of Jupiter, who often symbolized Louis XIV in this period; the substitution asserts the ability of the local government rather than the Crown to take care of its subjects in need.<7> In Rennes, Lully’s Atys was performed in 1689 to celebrate the return of the city’s parlement from an exile to which the king had banished it over a decade earlier following a local revolt; this production is by far the most explicit example of a Lully opera used as royal propaganda in the provinces.<8> In 1730s Strasbourg, Lully’s operas were abbreviated to bare minimums of storyline and music. The brusque treatment of Lully’s operas mirrors the cultural resistance that the historically Germanic city felt towards the French Crown, which had annexed Strasbourg in 1681.<9>

Beyond teasing out political struggles over absolutism in provincial opera productions, my dissertation also traces changes that provincial artists made to Lully’s libretti and scores. Opera performances in Lyon are the most richly documented of all provincial Lully productions, thanks to individuals such as Nicolas Bergiron (1690-1768), who curated the performance scores used by the Lyon Académie des Beaux-Arts, a semi-amateur music society. From these scores, we learn, for instance, that Lyonnais musicians did not hesitate to rewrite Lully’s continuo lines or shrink his expansive choruses into less time-consuming affairs. Such changes underscore not so much the mutability of the tragédies, but their locality – that is, how the operas were local phenomena that adapted fluidly to local ideas and tastes.

By exploring the locality of Lully’s tragédies, we expand the network of actors involved in the performance history of this repertoire to encompass singers, directors, and printers who operated beyond Paris, as well as government officials whose ideologies might have influenced the production of an opera. We also push issues of performance to the center, especially in instances where it might seem difficult or impossible to talk about the music: even though the scores of most provincial productions of Lully’s operas have been lost, there are clues in provincial libretti for alterations to Lully’s scores that diverged from how the repertoire was performed in Paris. The canonic narrative of French baroque opera – at least the narrative that we tend to teach in the classroom – often overlooks the locality of the tragédie en musique. We tend to imagine early French opera as a genre that was as rigidly centralized as the absolutist regime of the Sun King. By taking provincial productions of Lully’s operas into account, we gain a clearer understanding of how politics shaped opera – and vice versa – beyond Versailles in Old Regime France.

***

<1>Several historical studies have been particularly influential to my understanding of absolutism as a process of compromise and negotiation during the reign of Louis XIV. These include Roland Mousnier, La vénalité des offices sous Henri IV et Louis XIII (Rouen: Éditions Maugard, 1945); William Beik, Absolutism and Society in Seventeenth-Century France: State Power and Provincial Aristocracy in the Languedoc (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1985); and Junko Thérèse Takeda, Between Crown and Commerce: Marseille and the Early Modern Mediterranean (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

<2>For further details on absolutist propaganda under Louis XIV, see esp. Peter Burke, The Fabrication of Louis XIV (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

<3>For a concise reading of the politics of Quinault’s libretti, see esp. Buford Norman, Touched by the Graces: the Libretti of Philippe Quinault in the Context of French Classicism (Birmingham, AL: Summa Publications, 2001).

<4>For an overview of Lully’s monopoly, see Caroline Wood, French Baroque Opera: A Reader (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2000), 6; 8.

<5>For a chronology of performances of Lully’s operas outside of Paris, see Carl Schmidt, “The Geographical Spread of Lully’s Operas during the Late Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries: New Evidence from the Livrets,” in Jean-Baptiste Lully and the French Baroque: Essays in Honor of James R. Anthony, ed. John Hajdu Heyer (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 183-211.

<6>Pierre Gautier, Le Triomphe de la Paix (Lyon: Thomas Amaulry, 1691); Gautier and Balthazar de Bonnecors, Le Jugement du Soleil. Mis en Musique (Marseille: Pierre Mesnier, 1687).

<7>Marc Antoine Legrand, La Chûte de Phaëton, comédie en musique (Lyon: Thomas Amaulry, Hilaire Baritel, Jacques Guerrier, 1694).

<8>Jean-Baptiste Lully, Philippe Quinault, and Pascal Collasse, Atys, tragédie en cinq actes, avec un prologue mis en musique par M. Collasse, représentée à Vitré devant MM. des États de Bretagne, en 1689 (Paris: C. Ballard, 1689).

<9>See, for example, Lully and Quinault, Isis (Strasbourg: Jean-François Le Roux, 1732).

***

![]() Natasha Roule received her PhD in historical musicology from Harvard University in May 2018, where she was supported by a Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Completion Fellowship and an American Graduate Fellowship from the Council of Independent Studies.

Natasha Roule received her PhD in historical musicology from Harvard University in May 2018, where she was supported by a Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Completion Fellowship and an American Graduate Fellowship from the Council of Independent Studies.

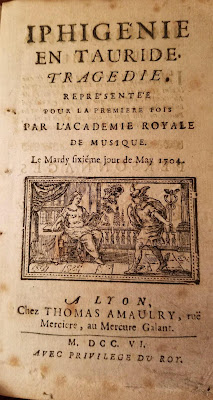

Title-piece from an opera libretto printed in Lyon in 1706.

Photo: Natasha Roule. From the author’s collection.

In 2015, Canal+ aired the first episode of Versailles, a Franco-Canadian television series about the young Louis XIV and his efforts to consolidate political power. As the title of the series suggests, Versailles centers its plot around the luxe chateau that the Sun King built on the site of his father’s favorite hunting lodge some 50 miles southwest of Paris. A dramatized historical fiction, the series draws from the vast historiographical literature that explores how Louis XIV cultivated his power from the seat of Versailles. Yet as the king worked to centralize the French government, he had to contend with a large kingdom beyond Versailles – a kingdom characterized by political and cultural heterogeneity that occasionally posed challenges to the king’s absolutist measures. Indeed, the political centralization of France under Louis XIV was a tricky affair: far from simply demanding that legislature be put into effect in each province, the king and his ministers engaged in a game of compromise, negotiation, and sometimes coercion with city magistrates and provincial governors. Though the history of absolutism in French cities has received some study by historians, we can gain a deeper understanding of the implementation and reception of absolutism in provincial France by approaching the subject from a musicological perspective.<1> To do this, the tragédie en musique– the absolutist genre par excellence– is key.

In my dissertation, “The Operas of Jean-Baptiste Lully and the Negotiation of Absolutism in the French Provinces, 1685-1750,” I explore the performance history of Lully’s tragédies en musique in four French cities: Marseille, Lyon, Rennes, and Strasbourg. I argue that productions of Lully’s operas in these cities played a major role in the expansion of absolutism even as they functioned as mouthpieces of provincial pushback against the Crown. On the one hand, Lully’s tragédies acted as vehicles of absolutist propaganda, lending mobility to the king’s image as an absolutist monarch in much the same way as the equestrian statues of Louis XIV that were erected in major cities throughout France.<2> At the same time, many provincial artists altered or satirized Lully’s tragédies, deliberately keying their modifications to critique royal intervention in local affairs.

Musicologists have long acknowledged the political bent of Lully’s operas. Lully (1632-1687) was the surintendant de la musique of Louis XIV and is credited with the invention of French opera, along with his librettist Philippe Quinault. With the king as his patron, the Italian-born composer ensured that references to Louis XIV and his sovereignty were woven throughout his own tragédies, from heroes who preach the importance of duty to choruses that explicitly applaud the monarch.<3> During his lifetime, Lully held a monopoly over the performance of opera that effectively restricted opera production to Paris and the court, where Lully worked.<4> It was not until after Lully’s death in 1687 that theaters across the kingdom began to produce opera, with the exception of the Académie de Musique of Marseille, which was founded with Lully’s permission in 1684. Even after opera spread to the provinces, few works besides Lully’s tragédies were performed until about 1700, a testimony to the composer’s enduring command over the French musical landscape.<5>

Marseille, Lyon, Rennes, and Strasbourg had unique cultural, linguistic, and political profiles that shaped local responses to Lully’s operas. In Marseille, Pierre Gautier, founder of the Marseille Académie de Musique, composed two operas modeled after Lully’s tragédies that asserted the city’s simultaneous loyalty to the absolutist Crown as well as its adherence to its historically civic republican identity.<6> In Lyon, parodies of Lully’s operas performed in the 1690s coincided with the city’s struggle to recover from famine and contagion without significant aid from the Crown. In a parody of Lully’s Phaëton, the character of a Lyonnais municipal sergeant replaces that of Jupiter, who often symbolized Louis XIV in this period; the substitution asserts the ability of the local government rather than the Crown to take care of its subjects in need.<7> In Rennes, Lully’s Atys was performed in 1689 to celebrate the return of the city’s parlement from an exile to which the king had banished it over a decade earlier following a local revolt; this production is by far the most explicit example of a Lully opera used as royal propaganda in the provinces.<8> In 1730s Strasbourg, Lully’s operas were abbreviated to bare minimums of storyline and music. The brusque treatment of Lully’s operas mirrors the cultural resistance that the historically Germanic city felt towards the French Crown, which had annexed Strasbourg in 1681.<9>

Beyond teasing out political struggles over absolutism in provincial opera productions, my dissertation also traces changes that provincial artists made to Lully’s libretti and scores. Opera performances in Lyon are the most richly documented of all provincial Lully productions, thanks to individuals such as Nicolas Bergiron (1690-1768), who curated the performance scores used by the Lyon Académie des Beaux-Arts, a semi-amateur music society. From these scores, we learn, for instance, that Lyonnais musicians did not hesitate to rewrite Lully’s continuo lines or shrink his expansive choruses into less time-consuming affairs. Such changes underscore not so much the mutability of the tragédies, but their locality – that is, how the operas were local phenomena that adapted fluidly to local ideas and tastes.

By exploring the locality of Lully’s tragédies, we expand the network of actors involved in the performance history of this repertoire to encompass singers, directors, and printers who operated beyond Paris, as well as government officials whose ideologies might have influenced the production of an opera. We also push issues of performance to the center, especially in instances where it might seem difficult or impossible to talk about the music: even though the scores of most provincial productions of Lully’s operas have been lost, there are clues in provincial libretti for alterations to Lully’s scores that diverged from how the repertoire was performed in Paris. The canonic narrative of French baroque opera – at least the narrative that we tend to teach in the classroom – often overlooks the locality of the tragédie en musique. We tend to imagine early French opera as a genre that was as rigidly centralized as the absolutist regime of the Sun King. By taking provincial productions of Lully’s operas into account, we gain a clearer understanding of how politics shaped opera – and vice versa – beyond Versailles in Old Regime France.

***

<1>Several historical studies have been particularly influential to my understanding of absolutism as a process of compromise and negotiation during the reign of Louis XIV. These include Roland Mousnier, La vénalité des offices sous Henri IV et Louis XIII (Rouen: Éditions Maugard, 1945); William Beik, Absolutism and Society in Seventeenth-Century France: State Power and Provincial Aristocracy in the Languedoc (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1985); and Junko Thérèse Takeda, Between Crown and Commerce: Marseille and the Early Modern Mediterranean (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

<2>For further details on absolutist propaganda under Louis XIV, see esp. Peter Burke, The Fabrication of Louis XIV (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

<3>For a concise reading of the politics of Quinault’s libretti, see esp. Buford Norman, Touched by the Graces: the Libretti of Philippe Quinault in the Context of French Classicism (Birmingham, AL: Summa Publications, 2001).

<4>For an overview of Lully’s monopoly, see Caroline Wood, French Baroque Opera: A Reader (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2000), 6; 8.

<5>For a chronology of performances of Lully’s operas outside of Paris, see Carl Schmidt, “The Geographical Spread of Lully’s Operas during the Late Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries: New Evidence from the Livrets,” in Jean-Baptiste Lully and the French Baroque: Essays in Honor of James R. Anthony, ed. John Hajdu Heyer (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 183-211.

<6>Pierre Gautier, Le Triomphe de la Paix (Lyon: Thomas Amaulry, 1691); Gautier and Balthazar de Bonnecors, Le Jugement du Soleil. Mis en Musique (Marseille: Pierre Mesnier, 1687).

<7>Marc Antoine Legrand, La Chûte de Phaëton, comédie en musique (Lyon: Thomas Amaulry, Hilaire Baritel, Jacques Guerrier, 1694).

<8>Jean-Baptiste Lully, Philippe Quinault, and Pascal Collasse, Atys, tragédie en cinq actes, avec un prologue mis en musique par M. Collasse, représentée à Vitré devant MM. des États de Bretagne, en 1689 (Paris: C. Ballard, 1689).

<9>See, for example, Lully and Quinault, Isis (Strasbourg: Jean-François Le Roux, 1732).

***

Natasha Roule received her PhD in historical musicology from Harvard University in May 2018, where she was supported by a Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Completion Fellowship and an American Graduate Fellowship from the Council of Independent Studies.

Natasha Roule received her PhD in historical musicology from Harvard University in May 2018, where she was supported by a Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Completion Fellowship and an American Graduate Fellowship from the Council of Independent Studies.