by David Gramit

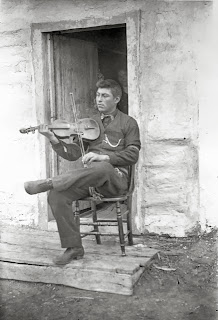

We don’t know much about the fiddler preserved in this turn-of-the-century photo from the Provincial Archives of Alberta (nor about the woman who peers evocatively from the shadows of the doorway of what we presume was his cabin). We know enough, though, to think that the notes that accompany the donation, describing it as an “Indian playing violin outside log cabin [1900],” are a revealing oversimplification. Both the act of fiddling and the man’s woven sash, visible at his waist and between his legs, reveal that he was very likely not a member of the Cree bands that inhabited the area of Edmonton in 1885, when George Ray, who collected this picture, took up his office as the first Registrar of Canada’s Northwest Territories (which then included present-day Saskatchewan and Alberta). Rather, he is Métis, part of a nation descended from the union of First Nations women with mostly French and Scottish fur traders, a nation whose culture includes a distinctive and still active fiddling tradition.

(For a brief sketch of music—including that of the Métis—in the Canadian west earlier in the century, see Daniel Laxer’s article on the soundscape of painter Paul Kane’s journey across Canada in the mid-1800s. Kane’s painting of Fort Edmonton is the iconic image of the fur-trading outpost that preceded the city.)

Why does this mislabeling matter? Because the myth of an empty land, inhabited by only a few wandering tribes of savage Indians, became foundational to the settlement of Canada’s “last best west,” just as it was across North America—so when Alberta became a province in 1905, in the midst of one of the continent’s last great settler booms, a souvenir booklet could tell of the “almost untouched unlimited resources of undeveloped wealth . . . of all those regions to which Edmonton is the gateway.” “Untouched” and “undeveloped” implied unlimited potential for profit, “and no one need hesitate to make his investments accordingly.” Like countless other variants of Wild West mythology, the booklet obscured an inconvenient truth: this was a land whose original inhabitants maintained a centuries-long tradition of trade and cultural interaction, a pattern of commerce in which Europeans were longtime participants but relative latecomers. Simplifications like the misrecognition of our unidentified Métis fiddler are both results of and contributors to that mythology.

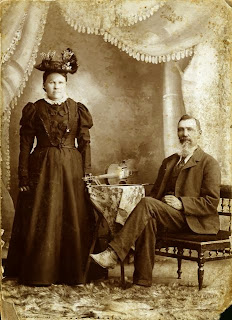

But when at least one other Métis fiddler represented himself, the resulting image was very different. The Edmonton city archives preserve this studio portrait of the prominent early Edmontonian Laurent Garneau and his wife Eleanor, taken around 1898. Born in Michigan around 1840 to a French Canadian fur trader and an Ojibway mother, Garneau was well known as a fiddler in the Edmonton area, where he had settled in 1874. Having fought with Métis leader Louis Riel in the Red River uprising of 1869 and then worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company, Garneau was intimately familiar with the political and social dividing lines of the west. Indeed, he had been arrested in 1885 at the time of the Northwest Rebellion, apparently because of his earlier association with Riel, and that same association thwarted his attempt to enter territorial politics in 1892. But Garneau still managed to become a respected figure in early Edmonton, achieving considerable wealth in a variety of business enterprises, and his portrait is structured to project propriety, achievement, and comfort in a settler’s world rather than his Métis heritage—even if he still valued his fiddle highly enough to place it on the table beside him. In short, this is not an image collected to record the customs of the locals, but a portrait of a couple who intend to be recognized as participants in a developing new society (one that within a few short years would be eager enough to distance itself from rural musical practices that a 1904 concert and dance ad for Edmonton’s Apollo Orchestra bluntly specifies: “no square dances”).

If admittedly remote Edmonton were a unique case, then these two images would be little more than curiosities of local history. But the city’s frantic growth (from just over a hundred when Garneau arrived, to 2,626 when he moved on in 1901, to more than 70,000 by 1914) was a late and relatively modest example of a development repeated across the west (and Australasia too) throughout the long nineteenth century, as James Belich has brilliantly documented in his Replenishing the Earth: The Settler Revolution and the Rise of the Anglo World, 1783–1939. These fiddlers and their tunes were local, to be sure, but the processes of displacement, explosive settlement, and cross-cultural negotiation to which they attest have their counterparts throughout the enormous settler-colonial world.

David Gramit is Professor of Music at the University of Alberta. He is author of Cultivating Music: The Aspirations, Interests, and Limits of German Musical Culture, 1770–1848 (University of California Press, 2002) and editor of Beyond “The Art of Finger Dexterity”: Reassessing Carl Czerny (University of Rochester Press, 2008). His research on music in early Edmonton is supported by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

(For a brief sketch of music—including that of the Métis—in the Canadian west earlier in the century, see Daniel Laxer’s article on the soundscape of painter Paul Kane’s journey across Canada in the mid-1800s. Kane’s painting of Fort Edmonton is the iconic image of the fur-trading outpost that preceded the city.)

Why does this mislabeling matter? Because the myth of an empty land, inhabited by only a few wandering tribes of savage Indians, became foundational to the settlement of Canada’s “last best west,” just as it was across North America—so when Alberta became a province in 1905, in the midst of one of the continent’s last great settler booms, a souvenir booklet could tell of the “almost untouched unlimited resources of undeveloped wealth . . . of all those regions to which Edmonton is the gateway.” “Untouched” and “undeveloped” implied unlimited potential for profit, “and no one need hesitate to make his investments accordingly.” Like countless other variants of Wild West mythology, the booklet obscured an inconvenient truth: this was a land whose original inhabitants maintained a centuries-long tradition of trade and cultural interaction, a pattern of commerce in which Europeans were longtime participants but relative latecomers. Simplifications like the misrecognition of our unidentified Métis fiddler are both results of and contributors to that mythology.

But when at least one other Métis fiddler represented himself, the resulting image was very different. The Edmonton city archives preserve this studio portrait of the prominent early Edmontonian Laurent Garneau and his wife Eleanor, taken around 1898. Born in Michigan around 1840 to a French Canadian fur trader and an Ojibway mother, Garneau was well known as a fiddler in the Edmonton area, where he had settled in 1874. Having fought with Métis leader Louis Riel in the Red River uprising of 1869 and then worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company, Garneau was intimately familiar with the political and social dividing lines of the west. Indeed, he had been arrested in 1885 at the time of the Northwest Rebellion, apparently because of his earlier association with Riel, and that same association thwarted his attempt to enter territorial politics in 1892. But Garneau still managed to become a respected figure in early Edmonton, achieving considerable wealth in a variety of business enterprises, and his portrait is structured to project propriety, achievement, and comfort in a settler’s world rather than his Métis heritage—even if he still valued his fiddle highly enough to place it on the table beside him. In short, this is not an image collected to record the customs of the locals, but a portrait of a couple who intend to be recognized as participants in a developing new society (one that within a few short years would be eager enough to distance itself from rural musical practices that a 1904 concert and dance ad for Edmonton’s Apollo Orchestra bluntly specifies: “no square dances”).

If admittedly remote Edmonton were a unique case, then these two images would be little more than curiosities of local history. But the city’s frantic growth (from just over a hundred when Garneau arrived, to 2,626 when he moved on in 1901, to more than 70,000 by 1914) was a late and relatively modest example of a development repeated across the west (and Australasia too) throughout the long nineteenth century, as James Belich has brilliantly documented in his Replenishing the Earth: The Settler Revolution and the Rise of the Anglo World, 1783–1939. These fiddlers and their tunes were local, to be sure, but the processes of displacement, explosive settlement, and cross-cultural negotiation to which they attest have their counterparts throughout the enormous settler-colonial world.

Provincial Archives of Alberta photo PAA A8125 and City of Edmonton Archives photo EA-58-3 appear with permission of the archives. The 1904 concert ad was located by Jamie Meyers-Riczu.

David Gramit is Professor of Music at the University of Alberta. He is author of Cultivating Music: The Aspirations, Interests, and Limits of German Musical Culture, 1770–1848 (University of California Press, 2002) and editor of Beyond “The Art of Finger Dexterity”: Reassessing Carl Czerny (University of Rochester Press, 2008). His research on music in early Edmonton is supported by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.