Last month after delivering a pre-performance lecture on Dayton Opera’s recent production of Madame Butterfly I lingered in the hall for a good twenty minutes chatting with patrons about all sorts of things related to the opera and my talk. A couple, maybe in their 70s, wanted to voice their opinions on the destructive forces of American imperialism and I was happy to listen. Another older gentleman shared with me his uneasy memories standing in front of a replica of the bomb that flattened Madame Butterfly’s hometown of Nagasaki, and Bockscar, the actual plane that dropped it at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, just five miles away from the opera house we stood in. For the past few years I have been delivering pre-performance lectures and schmoozing with patrons for the Dayton Opera, and I have thought of these engagements mostly as “public musicology”: an extension of my music history classroom, albeit for a slightly older audience. I have only recently thought about my teaching in the classroom as a form of public musicology, albeit for a slightly younger audience.

Public humanities projects, like The

National Endowment for the Humanities’ Common Good initiative, seek “to bring the humanities into the public square and foster innovative ways to make scholarship relevant to contemporary issues.” These projects are also usually broadly framed and interdisciplinary, bridging fields such as history, political science, and music as many fine contributions to this blog demonstrate. Shouldn’t music classes for undergraduate music majors and non-music majors alike strive toward similar goals? As I switch hats from the opera stage to the classroom I find myself asking the question: what differentiates public musicology from institutional instruction in musicology? Once we see these two spaces as connected (public and classroom) we can use public musicology as a pedagogical tool to help students think interdisciplinarily and to make connections between the study of music from the past and the performance of music in the present. It thus becomes an opportunity to create dialogue between and across disciplines, time, and individuals.

![]() |

| Homepage for the National Endowment of the Humanities Common Good Initiative |

Public musicology can be much more than sharing one’s research with the community, it can also be about sharing one’s teaching with the public as well. Musicologists such as

Craig Wright,

John Covach,

Thomas Kelly, and

Steve Swayne have opened up their classrooms to the world via the MOOC (Massive Open Online Courses). However, as the

hype of the MOOC dies down and the

media has all but stopped paying attention to what’s going on in these courses, perhaps we need to find some more low-tech and less costly ways to open up our musicology classrooms to the community. I’ll share some of my own efforts to meet these goals, not because I thought they always worked well (for the most part, they did), but I think we need to think more about the strategic public aims of our discipline and how they align with the goals of our courses. If we want to generate enthusiasm for our subject we can’t just look to the web and the season ticket holders of our local symphony/opera/ballet. We can and should also look within our own universities.

Dr. Laura Sextro, my colleague in the History Department, and I worked under the supervision and guidance of Dr. Ellen Fleishmann, another historian who serves as the

Endowed Alumni Chair of Humanities at our university, on a public humanities project tied to our teaching. We collaborated with other faculty across campus to commemorate the anniversary of The Great War through a series of curricular and co-curricular activities and used two of our courses as models for an interdisciplinary and collaborative public humanities project. My colleagues and I paired music majors in Music History II (Beethoven to Björk) with students from The History of Modern France. Music and history students engaged with the material analytically and experientially. Students stepped outside of the classroom to learn about the history and culture of this period by attending a series of co-curricular out-of-the-classroom events organized by the teaching team. After all, learning doesn’t just happen in the classroom. Public musicology is not just about the musicologist engaging with the public, but it is also about engaging students and the community together outside of the classroom.

So, on a brisk February Friday evening, over a hundred students, faculty and community members gathered dressed in glittery flapper gowns to dance two-steps, rags, and Charlestons for a World War One-era Social Dance Party. Most of the people in attendance were not enrolled in either course. They were not forced to be there, they weren’t earning extra credit; they were just there to dance, maybe learn something new, and to have a good time. We provided snacks, vintage recordings, dance instruction and a roundtable discussion. What better way to get college students engaged then by having them

dance with each other? But we didn’t just get them to dance; we got them to reflect on that dancing experience. Facilitated by historians and philosophers they were able to apply their experiences to the present state of social dance at an American University: to twerking, grinding and other booze-fueled house party gyrations. The idea was to get them engaged: engaged with the material, the historiographic problems, the lives of people involved, but also engaged with each other.

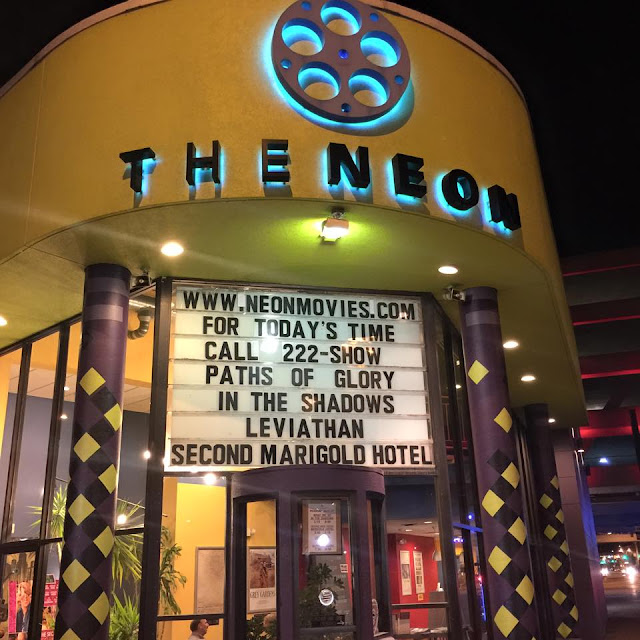

One of the other goals was to form connections between the music majors and the historians. The “Public humanities” are, after all, all about forming connections across disciplines. This is not just about doing interdisciplinary research or interdisciplinary activities in the classroom – it’s about working with actual human beings from other fields: colleagues who will enrich our musicological practice and carry the knowledge we share into their own disciplines. We took both classes to a performance of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem [photos], and rented out the local art-house movie theater for a special screening of Paths of Glory (1957) free to the public and to our students. We also carefully interspersed our students with the seating arrangements. Music majors had to sit with historians, and they talked! Both the concert and the film provided models for the students for their future presentations in the ways evidence needed to be presented.

The final project was a public lecture/recital where students of history and music worked in teams to present on music, history, culture, and war in WWI for the whole university community. Students spoke on topics including trauma in the trenches, emotion and memory after the war, nationalism, race on the battlefront, and the gendering of the homefront. The event included performances of Ives, Debussy, as well as popular songs of the period. In many of their final papers, students brought the music and culture of WWI into dialogue with current events through the comparison of nascent music therapy practices in the years after the Great War to current trends in treating PTSD in veterans of the Global War on Terror.

Music students reported that they found these co-curricular activities exciting, engaging, and helpful in working with the history students and in completing their own independent research projects. A music student wrote, “Even though we may not have been involved in writing each others papers, their ideas about history helped inform our ideas about music.” A student in the history class reflected on the lecture-recital by saying of her new friends in music, “They were lovely to work with; they were so nice and willing to seek similarities between our topic and theirs. They chose a great song to perform that worked so well with the points we wanted to make about history.” A number of student papers in Music History also demonstrated a deep interdisciplinary engagement with historiography thanks to the collaboration with students in History of Modern France. At the end of the semester students in the History of Modern France course engaged in experiential learning (dancing, attending concerts and special film showings) that most history classes would not include. Significantly, students explored ways in which musical works and musical performances engage with historical questions. Historians realized that music can be an important artifact for analysis: as a primary source, but also as experiential. My music majors were introduced to the social theory side of history, the study of war, and political and diplomatic history.

![]() |

| University of Dayton History Department faculty members dressed up for the WWI-era Social Dance Party on February, 2015. |

Most importantly, though, both classes developed academic and collegial friendships. They shared their bibliographies so that the lecture recital and individual final papers reflected an integrated familiarity with music history and history. The students were the ambassadors to each other and the public who attended their lecture-recital. They were the ones who ultimately made music/history more accessible, more engaging, and more relevant to contemporary issues. All of our students can do this. Just as a pre-performance lecture before Madame Butterfly can instigate a discussion on the proximity of war, trauma, memory, art and display, so can our students bring musicology together with other disciplines to perform public musicology for their own communities.