Editor's note: November 22 this year is Benjamin Britten’s 100th birthday, to be commemorated in a series of posts beginning tomorrow. For people of my generation—60-somethings—that date has another, indelible, meaning, since the day 50 years ago when school was interrupted by principals announcing the news, followed by a seemingly endless week of uncomprehending Americans glued to their (black-and-white) tvs. I’d rather remember the thrill.

Chill already. The yes-but essays on the Kennedys' Camelot (ex. 1, ex. 2, ex. 3) wrongfully deny the aptness of a rather touching metaphor in which we would do far better simply to delight. Mrs. Kennedy famously developed the notion of Camelot in an interview she gave Theodore White, just after returning to Hyannis from the funeral, for the December 6 issue of Life magazine. Kennedy had known Alan Jay Lerner at Harvard; the 1960 Broadway show had opened in Washington just as he was being sworn in. And, she said, they enjoyed listening to the record before bed. She said her husband was especially fond of the closing line, with its reference to “one brief, shining moment.” “There will be great presidents again,” she told White, “but there will never be another Camelot.” Good writing all around, I say: her construction had everything, including a title song.

- WOSU Camelot timeline

- James Piereson on Jackie Kennedy and the Camelot myth, Daily Beast, 12 November 2013

| Image may be NSFW. Clik here to view.  |

| John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum 2001 |

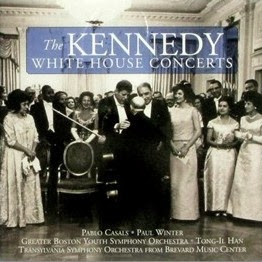

Especially, it was a matter of the concerts. The now-legendary concert by Pablo Casals, nearly 85, came in the first year, on November 13, 1961. (He had visited once before, in 1904, during the Theodore Roosevelt administration.) Coaxing him to Washington (despite the formal alliance of the US and Francoist Spain) was widely understood to have been the personal work of President Kennedy, whose remarks that night included specific welcome to representatives of what he called the world of Music and went on to resonate widely. “I think it is most important not that we regard artistic achievement and action as a part of our armor in these difficult days, but rather as an integral part of our free society.” Little matter that the president had needed coaching on exactly who Casals was (and Samuel Barber, and Aaron Copland).

| Image may be NSFW. Clik here to view.  | ||||||

| Robert Knudson, White House Photographs John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Musuem |

A year after Casals, on November 19, 1962, the Paul Winter Sextet, fresh from its State Department tour to South America, brought jazz (and bossa nova) to the White House.

“Simply wonderful,” says Mrs. K. “There has never been anything like it here before.”

And so much more. Dinner for Stravinsky (January 18, 1962). A lawn concert by the Greater Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra (April 16, 1962, in the cold, with the “New World” Symphony). The enabling legislation for the National Endowment for the Arts and what became the Kennedy Center. And the first class awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, shortly after the events in Dallas, which included Marian Anderson, Casals, and Rudolf Serkin.

It’s a legacy not soon forgotten. The Kennedy Center's retrospective, “The Presidency of John F. Kennedy: A 50th Anniversary Celebration,” included tributes to the Casals concert (Yo-Yo Ma and Emanuel Ax; January 25, 2011) and that of Grace Bumbry (Denyce Graves; February 1, 2011). The good-music stations have done well. There have also been live performances of Roger Sessions’s commemorative Third Piano Sonata (1965) and at least one of Bernstein’s Third Symphony, “Kaddish,” with its loving dedication to the late president (Baltimore SO / Alsop / September 2012). Among the events in Dallas was a concert on November 3, 2013, by the University of North Texas College of Music, again referencing the Casals, Bumbry, and Paul Winter concerts at the White House.

For those of us who lived nearto, the Kennedys’ Camelot, where it came to good music, is as clear and true a memory as Leonard Bernstein and the Young People’s Concerts. A fond recollection of national intelligence and taste and beauty—yes, glamor. Something, indeed, of lasting consolation.

—DKH