by Philip Gossett

Editor's note: This is the second in a series of posts commemorating Verdi's bicentennial. Roger Parker's piece is available here.

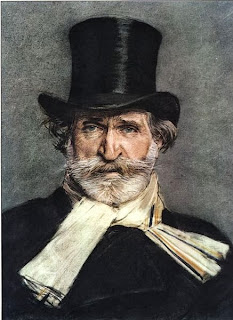

And so, we celebrate this year the 200th anniversary of Giuseppe Verdi’s birth. Why does it matter? Because Verdi is a composer whose work still dominates opera houses throughout the world and whose music is beloved by people across the globe, and the effect of these operas shows no sign of diminishing, even as Western classical music is heard less and less in Europe and America. They are beloved because the stories Verdi tells by means of his music and librettos have implications that touch all our lives. When he says in countless letters that most of his librettists were simply “versifiers” and not creators of the dramas he sets to music, he is right.

We don’t have to know the details of Rigoletto’s story to understand the deep love and incomprehension between a father and his daughter, nor must we know the details of Il trovatore to grasp the underlying truth of Manrico’s feeling for the woman he believes to be his mother, We do not need to know that Violetta was a prostitute to understand Alfredo Germont’s love for this woman nor Giorgio Germont’s concerns for the happiness of both his children. In pieces such as I Lombardi alla prima crociata and Aida, Verdi explores feelings of racism and religious intolerance that are still with us today, and when Giselda sings “Dio non lo vuole” as the crusaders kill the Muslims she is speaking directly to those of us who lived through September 11. We can share the thoughts that King Philip expresses about the conflicts between the church and the state We must accept Falstaff’s final fugue, “Tutto nel mondo è burla,” not as a statement about Falstaff, but as a statement about the human condition more generally. Yes, much of the composer’s final opera is derived from a play by another genius, Shakespeare, and in this case Verdi had a great librettist in Arrigo Boito, but it is Verdi’s music that we come back to again and again.

Verdi’s genius lay in his extraordinary ability to speak to the human condition. It may be that, as scholars, we want to know exactly how his treatment of Ernani differs from the play by Victor Hugo. We want to know the history of Giovanna d’Arco and La forza del destino, we want to understand what Spanish Romanticism was like, and we care about the differences between various states of Un ballo in maschera, but the public really doesn’t care whether they had masked balls in Puritan Boston or not. As Verdi himself said, what mattered to him was the truth of the situations and the characters he sought to present, not exactly where a story was located. We may be concerned about questions of the words being sung and just how the censors tried to devastate his operas, without success, but we know that our queries do not affect most opera lovers. We want to know what he wrote, when he wrote it, and in what language he wrote it, even though we know that most lovers of the operas couldn’t care less. That is as it should be. We cannot assume that the questions that occupy the attention of musicologists will be of universal concern, but we know that the operas of this composer are universal in the best possible sense.

There are very few artists indeed who have this level of importance for the world. It is also the 200th anniversary of the birth of Richard Wagner, and Verdi knew that Wagner’s operas had a special place in the theatrical world, indeed in the whole history of art. And yet, for all we may seek to generalize Wagner’s importance, he remains a very different kind of composer from Verdi. Of course he mattered, but in a different, perhaps less human way than Verdi. We are astonished at the quality of Wagner’s invention and there are scenes we will always treasure, like Wotan’s farewell to his daughter, but we are moved by Verdi’s operatic invention and know that he kept at it from the late 1830s through 1893, a long period by anyone’s reckoning.

I write this from New York, where the American Institute of Verdi Studies is holding a conference in honor of Verdi’s birthday. It is clear that the kind of questions that occupied scholars of my generation are not particularly relevant to scholars of today. They are more interested in learning how today’s stage directors and film directors approach Verdi’s music, and that too is as it should be. Each generation will identify different questions to explore, but the operas maintain themselves no matter how we interrogate them. And Verdi was important also for patriotic reasons: Italy, which could not hope to compete in the world arena for its military prowess or its economic strength, has proven itself a center for the arts. A country that could produce Dante, Machievelli, Monteverdi, Manzoni, and, yes, Verdi, is a country that matters in the world and will continue to matter as long as there are people who care about matters pertaining to the soul. I trust that in another hundred years we will be celebrating the 300th anniversary of the composer’s birth with as much enthusiasm as we experience today.

Philip Gossett is Robert W. Reneker Distinguished Service Professor of Music, emeritus, at the University of Chicago and a former president of the American Musicological Society. He is general editor of the critical editions of both Verdi and Rossini.

Editor's note: This is the second in a series of posts commemorating Verdi's bicentennial. Roger Parker's piece is available here.

And so, we celebrate this year the 200th anniversary of Giuseppe Verdi’s birth. Why does it matter? Because Verdi is a composer whose work still dominates opera houses throughout the world and whose music is beloved by people across the globe, and the effect of these operas shows no sign of diminishing, even as Western classical music is heard less and less in Europe and America. They are beloved because the stories Verdi tells by means of his music and librettos have implications that touch all our lives. When he says in countless letters that most of his librettists were simply “versifiers” and not creators of the dramas he sets to music, he is right.

We don’t have to know the details of Rigoletto’s story to understand the deep love and incomprehension between a father and his daughter, nor must we know the details of Il trovatore to grasp the underlying truth of Manrico’s feeling for the woman he believes to be his mother, We do not need to know that Violetta was a prostitute to understand Alfredo Germont’s love for this woman nor Giorgio Germont’s concerns for the happiness of both his children. In pieces such as I Lombardi alla prima crociata and Aida, Verdi explores feelings of racism and religious intolerance that are still with us today, and when Giselda sings “Dio non lo vuole” as the crusaders kill the Muslims she is speaking directly to those of us who lived through September 11. We can share the thoughts that King Philip expresses about the conflicts between the church and the state We must accept Falstaff’s final fugue, “Tutto nel mondo è burla,” not as a statement about Falstaff, but as a statement about the human condition more generally. Yes, much of the composer’s final opera is derived from a play by another genius, Shakespeare, and in this case Verdi had a great librettist in Arrigo Boito, but it is Verdi’s music that we come back to again and again.

Verdi’s genius lay in his extraordinary ability to speak to the human condition. It may be that, as scholars, we want to know exactly how his treatment of Ernani differs from the play by Victor Hugo. We want to know the history of Giovanna d’Arco and La forza del destino, we want to understand what Spanish Romanticism was like, and we care about the differences between various states of Un ballo in maschera, but the public really doesn’t care whether they had masked balls in Puritan Boston or not. As Verdi himself said, what mattered to him was the truth of the situations and the characters he sought to present, not exactly where a story was located. We may be concerned about questions of the words being sung and just how the censors tried to devastate his operas, without success, but we know that our queries do not affect most opera lovers. We want to know what he wrote, when he wrote it, and in what language he wrote it, even though we know that most lovers of the operas couldn’t care less. That is as it should be. We cannot assume that the questions that occupy the attention of musicologists will be of universal concern, but we know that the operas of this composer are universal in the best possible sense.

There are very few artists indeed who have this level of importance for the world. It is also the 200th anniversary of the birth of Richard Wagner, and Verdi knew that Wagner’s operas had a special place in the theatrical world, indeed in the whole history of art. And yet, for all we may seek to generalize Wagner’s importance, he remains a very different kind of composer from Verdi. Of course he mattered, but in a different, perhaps less human way than Verdi. We are astonished at the quality of Wagner’s invention and there are scenes we will always treasure, like Wotan’s farewell to his daughter, but we are moved by Verdi’s operatic invention and know that he kept at it from the late 1830s through 1893, a long period by anyone’s reckoning.

I write this from New York, where the American Institute of Verdi Studies is holding a conference in honor of Verdi’s birthday. It is clear that the kind of questions that occupied scholars of my generation are not particularly relevant to scholars of today. They are more interested in learning how today’s stage directors and film directors approach Verdi’s music, and that too is as it should be. Each generation will identify different questions to explore, but the operas maintain themselves no matter how we interrogate them. And Verdi was important also for patriotic reasons: Italy, which could not hope to compete in the world arena for its military prowess or its economic strength, has proven itself a center for the arts. A country that could produce Dante, Machievelli, Monteverdi, Manzoni, and, yes, Verdi, is a country that matters in the world and will continue to matter as long as there are people who care about matters pertaining to the soul. I trust that in another hundred years we will be celebrating the 300th anniversary of the composer’s birth with as much enthusiasm as we experience today.

Philip Gossett is Robert W. Reneker Distinguished Service Professor of Music, emeritus, at the University of Chicago and a former president of the American Musicological Society. He is general editor of the critical editions of both Verdi and Rossini.